Economic justice and climate justice are not metaphors: A response to Justice Creep by Scott Alexander

I

Scott Alexander has a new blog post up in which he complains about a phenomenon he calls justice creep. A move in language away from talking about how it would be nice to help certain groups or causes, to talking about securing justice for those causes:

Helping the poor becomes economic justice. If they’re minorities, then it’s racial justice, itself a subspecies of social justice. Saving the environment becomes environmental justice, except when it’s about climate change in which case it’s climate justice. Caring about young people is actually about fighting for intergenerational justice. The very laws of space and time are subject to spatial justice and temporal justice.

But I disagree. I don’t object to Justice Creep. Regardless of whether it is useful -and I hope it is- I think that honesty compels a clear-eyed person to talk about many of these things in terms of justice, even in the narrowest conception of justice.

The mistake in Scott’s article is assuming that these forms of justice are merely metaphors or analogies on criminal justice. Many of these are about justice in exactly the same sense that crimes are about justice- no metaphor required. Of course, they are also about being just in other senses- justice was never just about crime. For example, one can detect demands for social justice in the bible that go far beyond "wouldn't it be nice to help people", but nonetheless aren’t framed in terms of the criminal law.

Nevertheless, yes, climate justice and economic justice- for example- are also about being just in the same way laws against murder are- no stretching of meaning is required. Unfortunately, this point often becomes lost due to something I call the legal veil. The legal veil prevents us from fully grasping the moral dimensions of actions that are officially sanctioned. Instead, we assess them in a dreamlike manner- they become “regrettable”, “scandals” etc. but stop being crimes.

Let us briefly define terms.

An issue of justice, in the same sense of justice as criminal justice, arises when one person foreseeably harms another, or when one person threatens another with harm.

An act is unjust, in the same sense criminal acts are unjust, when the harm, or threat of harm, cannot successfully be defended as right or necessary e.g. an unjust act is an issue of justice per the above definition, that cannot be successfully defended.

II

My point is perhaps best first illustrated by a point not from Scott's essay, but from one of the comments on the Reddit thread about the article. The author of the comment lists instances of "hyperbole" that they think are plaguing contemporary discourse. One of the examples is referring to the Iraq war as a "war crime".

I want you to imagine a post-apocalyptic society, say the burnt-out ruins of Sydney. There's a gang in Darlinghurst with 30,000 members and a gang in Haberfield with 4000 members. The gang with 30,000 members has knives and baseball bats and even a few score guns, the gang with 4000 members has big sticks. The gang with 4000 members is ruled by a brutish fellow- not well-liked. A rumor starts about him that he is building some guns- soon the gang with 4000 members might have guns of their own. The leader of the gang with 30,000 members drums up panic about this fellow's guns of mass destruction. Eventually, he leads an attack on the gang. A hundred members of the smaller gang die. It turns out the smaller gang didn't have guns.

There are, as far as I can tell, zero moral differences between the situation I have described and the Iraq war. To the degree that there is a difference, the Iraq war is actually worse, because people had more opportunity to be civilized given that we're not in a post-apocalyptic hellscape.

So why do people think of calling the Iraq war a war crime "hyperbole"? Because our brains treat formally illegal things as beyond the pale but treat violations of morality under color of law as "issues" "scandals" "tragedies". We place a veil of law over them, which subdues the moral wrongs. But surely, on any consistent moral view, this veil of law is a fiction. I wrote about this in an essay once called A Katana, an iron bar and prison. The gist of it is, suppose you met a judge at a cocktail party who had, in your opinion, punished someone harshly in an obviously unjust way. you should treat that judge like you would treat a person who had beaten someone viciously with an iron bar for no good reason or more accurately, locked someone in his own basement for a decade. However, because the act was done through the "appropriate channels", they are protected by a moral blindspot. Moral maturity means recognizing that the moral veil is fiction, although perhaps -tragically- it might be necessary and useful in some ways.

III

Now, to Scott's examples. Let's start with Climate Justice

There's a room. In that room are people sitting at different elevations. There are delicious macaroons laid out on the tables. Every time a person eats a Macaroon a little bit of a poisonous gas heavier than oxygen enters the room. Nonetheless, many people, disproportionately those at higher elevations, continue to eat Macaroons. The people at lower elevations are begging, pleading, screaming, and sobbing for the macaroon eaters to stop eating so many macaroons but it's just so difficult to coordinate everyone to stick to a macaroon budget, and besides, some people- including many suspiciously funded by the macaroon lobby- are arguing that the poisonous gas doesn't exist and... so on- I'm sure you get the metaphor. Talk of macaroon justice is talk of justice in exactly the same way criminal justice is talk of justice. When it comes to climate justice, just as in macaroon justice, assault, property damage even murderous wrongdoing is afoot. However the veil of law - of official permission for the actions of governments, fossil fuel companies, and big polluters- stops us from seeing that.

This is why Scott's question about the little ice age is a bit silly. The little ice age wasn't unjust, just like spontaneous perfusion into the macaroon room of poisonous gas wouldn't be unjust. What is unjust is power players using state and corporate power to allow and even violently defend macaroon consumption, even after the stakes become obvious.

But does that mean neglecting those suffering due to natural variation in climate is not unjust, as in Scott’s example of Mali? No, as we’ll see now in our discussion of economic justice.

IV

So what of economic justice? Step back and think about what property is. Stop thinking about it as an abstraction, and think about its real legal and social existence. Property is the right to exclude everyone else from using something under threat of violence unless they have your permission, or unless you transfer it to them as a gift or sale.

Now suppose you're dying in the snow. You walk up to a house and knock on the door pleading for shelter. A man with a shotgun greets you and tells you to fuck off. You do and die alone in the cold.

The distribution of property (which again is a social relation entailing the right to threaten someone with violence for using something) is a result of contrivances and power operations. Taxes and transfers and subsidies. At the end of the game of musical chairs, some people, whether through ill-luck, incompetence or in some cases the malice of others, are left with nothing. Surrounded like tantalus with things that could help them, but that they can never reach because men with guns from a large organized gang (the government) prevent them.

Now you may argue that the current distribution of property is fair (doubtful- I don't think it meets anyone's standards of fairness given how arbitrary many of the rules are). You may argue that the current distribution of property is necessary from a consequentialist perspective (again, doubtful. Iceland has one-third the relative poverty rate of the US- I'm sure the relative poverty rate could be cut at least in half). However even if it is both fair and necessary, the question of whether there is economic injustice is still a question of justice, even if the answer is everything is just. This is because it is a question of forceful coercion. Asking whether Bob is unjustly exploiting Ellen is little different in principle from asking whether Bob is assaulting Ellen- whether the answer is yes or no. Yet again the veil of law has blocked our sight. Although the consequences may not always be life and death, the question of property is not unlike being forced outside to die in the snow- or at least to suffer greatly.

Edit: I want to be super clear on something even to the point of repeating myself slightly. Nothing I said above commits me to the view that all property rights are bad. It only commits me to the view that property is a right to violently exclude. Sometimes that may be a necessity, perhaps for economic propensity, for privacy or even to avoid danger (as with property over a nuclear plant) etc.

Nor am I saying that property doesn’t exist, I’m just saying that to morally and politically evaluate property, you first have to get some distance from it by abstracting away from it, and analyzing what it is in real social terms. That means recognizing that property existence is not fundamental, but is made up certain kinds of arrangements of objects and people. What are those arrangements? In real social terms I think property is a relation of power over a thing, secured by power over other people- the power to exclude them from that thing. This power over others is often, but not always, mediated by state power.

V

Now as for saints and Scott's comment that this model of the world has no room for saints, I'd say this model of the world plenty of room for them. Heroes who stand up to moral criminals far more powerful than they are and risk reputation and life in the process are saints. As one commentator on the Reddit thread put it beautifully:

I’d think it would allow wise judges, paragons, righteous heroes, evil-slaying paladins, and so on?

To this list, we can add Martyrs. But we can also add in ordinary saints- saints of charity and not justice- the kind of saints that Scott complains this model does away with. Being charitable, kind, and merciful is nobler against a background of greed and malice.

But sainthood is about more than giving large sums of money philanthropically anyway. It’s always been about giving when it hurts and giving when giving takes courage. I’m reminded of the Widow’s mite:

"He sat down opposite the treasury and observed how the crowd put money into the treasury. Many rich people put in large sums. A poor widow also came and put in two small coins worth a few cents. Calling his disciples to himself, he said to them, 'Amen, I say to you, this poor widow put in more than all the other contributors to the treasury. For they have all contributed from their surplus wealth, but she, from her poverty, has contributed all she had, her whole livelihood. Mark 12:41-44

This quote from Archbishop Hélder Câmara

“When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist”

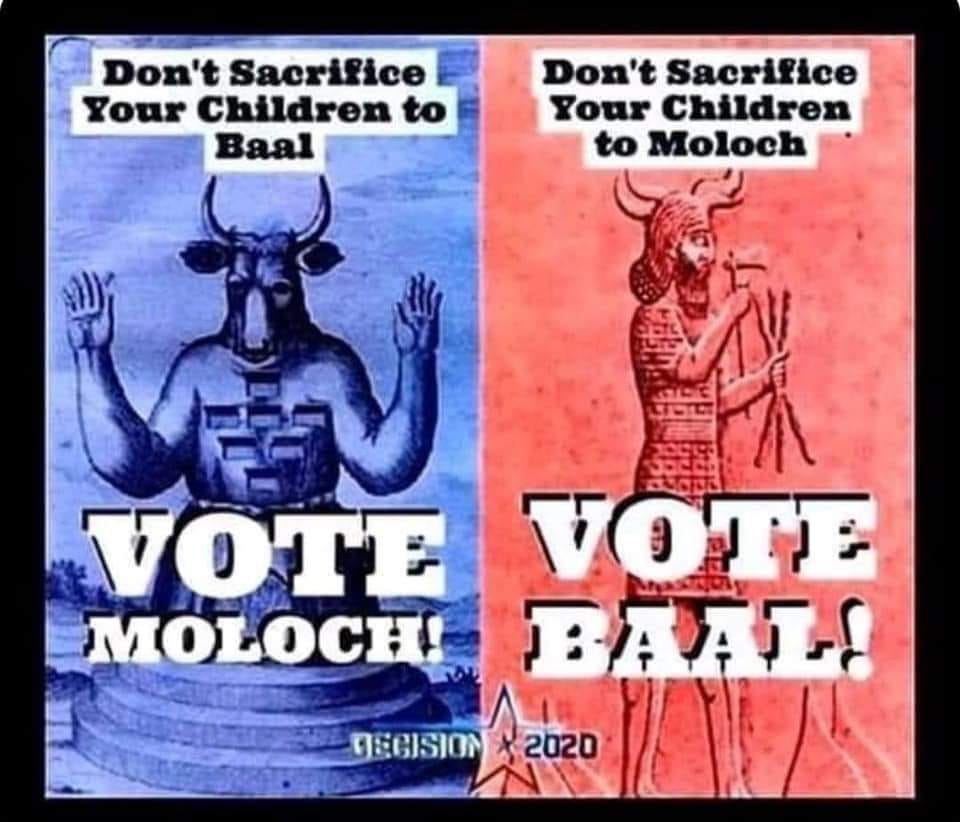

And strangely, this quote from Lowell, repeated extensively in Unsong

But the soul is still oracular; amid the market’s din,

List the ominous stern whisper from the Delphic cave within,—

‘They enslave their children’s children who make compromise with sin.’

But we’ve all made our own compromises with sin haven’t we? So please don’t take this as holier than thou preaching.

VI

Am I suggesting piercing the veil of law to a permanent end? Am I suggesting Nuremberg-type trials for, for example, "climate criminals"? Eh, probably not. But this isn't because there is no consistent standard under which these people deserve Nuremberg trials, it's just that I'm both merciful and practical. I don't like the idea of punishing anyone. I'm the kind of person who goes to bat for violent criminals, even the sort of violent criminals most of the left loves to hate. However, if I had a great deal of power, and if I were more vengeful than I actually am, it would be brutally apparent that there is zero mottes and baileys here. This is very directly about crime, and by clear implication, punishment.

Others that come after me and my generation might not be so merciful. Something “climate criminals” would do well to remember, especially those of them that are likely to be alive in thirty years or more when the worst effects have set in.

VII

Edit: This response is quite long because I want to be very precise. A reader writes in relation to my analogy of a man being forced into the snow:

You don't say what we're supposed to take from the analogy, but it seems like the implication is that this is unjust. But it would not be unjust by most normal understandings of the term. The man's actions are, under many moral frameworks, immoral, but that's not the same as being unjust.

But it seems to me that of course, this matter relates to justice. You’re being forced out into the snow to die. Generally, we’d call this murder. Being murdered is an injustice.

Now I don’t know why the reader thought this wasn’t an instance of injustice, but I can guess. They’ve assumed the house belongs to the gun yielder, ergo the gun wielder has a right to decide whether to let you in or not. Their action might be immoral, insomuch as it is a refusal to extend charity, but it is not injustice insomuch as it is not a breach of your rights. They have the right to the house. Things get tricky here because our intuitions about private property are very deep. I’m going to try to let you look at them from a distance.

The first thing to note is that I never said the house belongs to the gun wielder. That was a deliberate omission. I wanted to strip away all concepts of property. It is very interesting that the Redditor mentally inserted this though.

Before we get to the questions of the morality of property, there are only objects in the world, and people claim those objects by the threat of violence restricting the liberty of others to use them. Ownership is a social convention to use violence on people who try to use stuff that isn’t recognized, by the social convention, as their stuff. In the first instance -looking at the world without concepts of property-, this guy is a guy who is driving people out into the snow to die. Hence, prima facie, his actions are murder, unless they can be justified in some way.

Issues of economic justice are just that on a grander scale- debates over whether the violence used in pursuit of “ownership” are defensible in some particular case, or are instead indefensible restrictions on people’s liberty to use what they want to.

Now of course you could believe that private property exists as a moral right on top of this world with people, objects, and guns. You could also believe that private property means the man with the gun hasn’t acted unjustly so long as he owns the property. Fair enough. But that doesn’t stop being driven out onto the snow from being an issue of justice. It just means that it’s an issue of justice that resolves as “no injustice was done here”. The owner is charged with injustice but gets off on a private property defense. The accusation of injustice is still not a metaphor.

On the other hand, people who don’t accept that anyone has the right to force people out into the snow [e.g me] will regard it as an issue of justice in which grave injustice has been done. I don’t think the man has any real moral right to the house in the sense needed to force someone outside, there’s just a social fiction that he does. That social fiction allows him to rationalize chasing someone into a place where they will die but makes no moral difference.

My personal view is that some forms of ownership -violent restrictions on the liberty of people to use things- are defensible, at least at this stage of history, but only if they ultimately serve a consequentialist greater good. Hence forcing someone outside into the snow to die just because you don’t want them to sleep in your house is murder, because it doesn’t serve the greater good. No laws change that, and in the true moral sense of ownership- a moral right to exclusion- you don’t own your house in that way.

I think this is a great post. I have quibble on the Iraq war example - I think it's highly relevant that Saddam had invaded both Kuwait and Iran unprovoked previously and had had and had used chemical weapons. I don't think this changes anything substantively in your argument, but I think it underplays the degree to which Saddam was a danger to international community.

After reading both posts, I think I agree more with you - we probably should consider more things as issues of justice, not fewer. I do still think it's pretty arbitrary how we chose to frame things - in a society with slightly different values (or even with the same values?) we could well be talking about social issues in terms of "Duty" or "Virtue" with much the same results, so I think it's just a matter of what we find most compelling. It may actually be worth considering whether different frames work better in different contexts or cultures? (e.g. Liberal vs Conservative, Eastern vs Western)

I do feel like there are issues with framing things in terms of justice though - it may constrain the scope of the problem too much, and encourage disengagement if you're just a regular person - after all, we leave justice to the justice system! As Scott observes, many people have a purely punitive conception of justice, so maybe environmental justice just looks like doing nothing until it's too late and then punishing a small number of people for our collective guilt, which is probably not going to help much. This is probably an issue with how we conceptualise justice more than anything else, but it is still worth considering.