Lifeboat ethics describes the ethics of a situation in which there is not enough of a critical good for everyone, and yet that resource has to be distributed. Some people will go without. How should we decide who gets what?

Let us define a term, topic-concern. Sometimes you don’t disagree with any position on the table regarding a topic but you find it notable that the topic is being discussed now. It’s not, necessarily, even that you disagree with discussing the topic, it’s just that there seem to be so very many discussions of that topic lately. It’s often hard to make this kind of metaphilosophical complaint in philosophy because philosophy tends to be tightly focused on the truth or falsity of specific propositions. This makes the question “but why talk about this, and not something else?” hard to raise. Yet it is so often the question I want to ask.

I feel this way about various lifeboat ethics discussions going on in philosophy related to how to split available goodies. Some practices (AA) I broadly support, and other practices (citation justice except in its weakest forms) I largely oppose, but I am averse to focusing my attention on any of them. It’s not that these discussions about how to split our bit of the pie are unimportant, but administrators have taken half the pie for themselves, and the pie itself is much smaller than it should be. As philosophers, we should have a lot to say about that.

Yesterday I went to an excellent talk by a philosopher Jessica Isserow on praise, a term she used to mean something quite broad- something like social credit assignment. She argued- and I agree- that praise cycles can develop. In any field, praise can lead a person both to more output and to more notice, which can lead to further praise. Although this process might seem meritocratic, a moment’s reflection suggests that it could make it very difficult to recover from even a small run of initial bad luck- whether in one’s work or life. Chance will play a great role, often in very cruel ways. Sometimes called the Matthew effect, Isserow, rightly I think, regards it as a wicked problem and one with implications for how we treat each other. Isserow doesn’t think she has an answer, but not unreasonably suggests we should practice at least being aware of, and looking out for others and their contributions thus far left behind by the spiral.

These topics are interesting for many factors, but I can’t help suspecting that one of the reasons we’re talking about this now is because the stakes for assigning credit in philosophy at the moment are very, very high. For some people, it means the difference between eating or not. I can’t help but notice that it is part of an enormous, blooming discussion in philosophy- public and behind closed doors- that relates, to some degree or another, to who gets what in philosophy itself. Examples:

Some aspects of the epistemic injustice literature

Citation justice and some aspects of the publication justice literature

Internal discussions about the distribution of available roles between quite different areas like Analytic and Continental philosophy

And public and private discussions about assigning jobs to candidates, affirmative action, etc.

A while ago a Daily Nous post, discussing a paper that found that women have a 58-114% higher chance of being hired came up again for extensive discussion. I was going to put together a take about the ethics of affirmative action, the extent to which hiring practices now should try to ‘compensate’ for previous hiring practices, etc.

Eventually, I decided not to. It’s not that I don’t have views on the appropriate approach to AA. I have a lot of thoughts:

I support affirmative action and I have a few ideas about how to balance the different goods against each other.

I resent that legal frameworks in some countries mean we can’t be open about doing AA. I think its ‘underground’ nature makes it more difficult to have precise discussions about it, and really get into the nitty-gritty of how it should be done. Ideally, I think we should set explicit quantitative targets or some kind of “additional points” system. I recognize these approaches have problems, but I suspect hiring generally should be a more open and accountable process, and this is part of that.

I feel that the informal way many discussions of affirmative action occur during the hiring process means that little weight is given to invisible or non-obvious forms of disadvantage. I deeply resent this, and any assumption that you can tell how easy someone has had it at a glance. I note that sometimes HR explicitly behind closed doors talks in terms of achieving visible diversity, which I think betrays the genuinely noble ideals of AA for marketing.

I think it is at least a little irritating that the very generation that benefited from explicitly or near explicitly racist and sexist hiring practices now gets to feel good about themselves for applying AA to new positions, their own jobs never threatened.

My spiciest take of all, marginally related to AA and likely to make people hate me and never going to happen anyway: if there isn’t enough money for academic jobs to go around, no academic should be earning more than about 100k US. I have a slightly monastic view of academia- we need to purge the people who see it as a road to conventional high status. To go into academia rather than industry should be seen as a choice to focus on the life of the mind. The kind of person who won’t join academia because there’s no chance that one day they’ll be earning 180k probably is probably no great loss. Maybe this is more true in the humanities than in, say, physics, where competition with industry is a problem- but at least around these parts, that is my sense of things.

But I have never written an article outlining my views on AA in academic hiring in general and I probably never will, despite some of those points (especially the one about visibility) being a huge bugbear for me.

The reason I’m not going to write a 6000-word screed on the topic is that I’m trying to practice what I preach. I try to focus on demanding many more academic jobs than worrying about how they are split. Call me naive but I believe what academics work on, yes, even the much-maligned humanities, matters, and that the marginal public benefit of an additional philosopher, or for that matter academic physicist, mathematician, historian, economist, anthropologist, biologist, or whatever else greatly exceeds the marginal cost but academics are undersupplied because their work is a public good, and in some cases a very abstract public. Public goods like this are undersupplied relative to their value due to the Samuelson Condition result. With E.g. philosophers, what you’re betting on are extremely rare breakthroughs that are often only apparent for what they are decades, or even centuries after the fact. I know that sounds insane, but c.f. the history of philosophy for evidence. Given what philosophers have done historically, I do not think that 6000 professional philosophers in the US and an estimated 20,000 globally is the right number.

Even if you do not believe that academic jobs are undersupplied I suspect you will at least agree with me that they are undersupplied relative to senior pro-vice deans for world’s best practice management excellence.

Now you might say “okay yes, more jobs would make things easier, but there are questions of structural injustice in distribution, and they won’t go away if there are more jobs”. This is true, and we should work on structural injustice, but the point no one ever seems to make in these discussion within philosophy is that structural injustice becomes less bad when labor markets are tight, and the ratio of positions to applicants is higher. A talented person whose career was interrupted by, say, mental illness or domestic violence? Much more likely to get a job if there are enough jobs available that you can get one even if you haven’t been sigma-grindsetting your way through publishing three papers a year every year. People who face background disadvantages throughout their entire life? Also likely to benefit from the breathing room that more spaces offer. The justest job markets we have are tight job markets. Tight job markets give second chances for those left behind through unfair disadvantages, tight job markets tend to equalise wages, tight job markets make companies treat their employees right, and make it more difficult for employers to use sexism etc. to their advantage.

If God said you could implement one single, simple policy in academia, and your sole goal was to reduce structural injustice, that policy would be to increase the number of spots available.

So what if, instead of thinking about how we regulate ourselves given the absurdly small number of lifeboats available, we turn the weapon of criticism, in combination with the more effective weapon of organization, against the bastards?

Now you might be thinking “Philosophy Bear, it’s an unfortunate reality that there aren’t enough spots in academia, but philosophers can’t talk about it indefinitely because there’s not much more to say about it. It’s bad sure but you can’t just write an unlimited number of papers saying something is bad.”

Here are, off the top of my head, some areas philosophers could work on if they’re interested in the problems I’ve outlined. It’s not hard to come up with an essentially unlimited number of them:

Academic and student control of universities- prospects, pitfalls, and concrete proposals.

The ethics of industrial action for workplace democracy and greater hiring

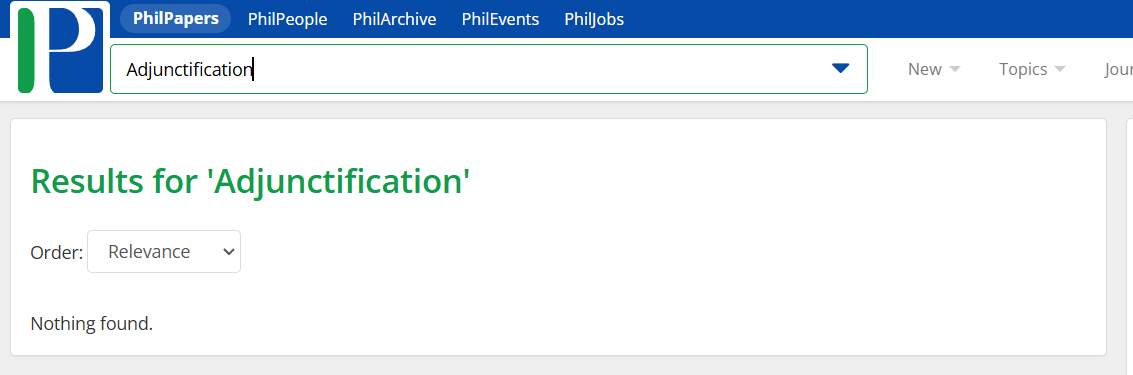

Adjunctification as injustice

Philosophical and social-epistemological critique of the administrator category

Philosophical questions around the nature of positive externalities and public goods coming from intellectual work.

The exploitative character and injustices of an economic system that operates like a pyramid scheme, vis a vis, the use of graduate student labor.

Concrete work to try and make it easier for people who have been pushed out of academia by the job market to keep publishing if they feel they have something they want to say about philosophy- to make them welcome at conferences and talks etc.

There is work on these topics- but not enough!

When I put this to Isserow she responded that the problems she is working on would be real even if there were an infinite number of philosophy jobs. And I agree, that’s absolutely true, and I in no way oppose her doing this work which I think is superb. it’s just that there are so very many people working on topics that happen to be to some degree or another relevant to lifeboat ethics, and who should get what. And there are so few people working on making the case for more lifeboats. So to repeat myself and be painfully clear, because I don’t want to dismiss anyone’s work, the problem isn’t this specific bit of research, which is great, and which has implications far beyond lifeboat ethics, it’s that when you take the picture as a whole, the ratio of:

Work relevant to who gets what in philosophy to work relevant to the deficit of support for intellectual life

Is so very high.

Finally, I’m sure it’s obvious, but let me be clear that I’m not suggesting that philosophers self-indulgently focus the bulk of their attention on their own plight. Only a small proportion of our output should be devoted to these matters- but to the extent we talk directly about, and shadowbox around, the problem of the lifeboats, let us never forget to demand more.

The praise problem is simple and obvious when you look at popular science books. Regardless of the original pedigree, a person's work which is noticed once gets them granted acclaim again and again. It's the noticing that does the work. They are given grants and awards and honorary degrees not because they are better than others in their field but bc they came to the attention of those who gatekeep the accolades. In essence, they are rewarded for having been previously rewarded.

A great many problems in academia would indeed be solved by simply opening up more permanent full-time faculty positions (not even necessarily tenure-track, just permanent). But that would require laying off administrators or reducing their salaries, which those same administrators don't want to do. (Or raising tuition, which is already sky-high.) And despite the poor working conditions for new faculty, there doesn't seem to be any shortage of new applicants, so universities have little incentive to change.

I find your ethical argument compelling, but the economic incentives are all wrong to make it happen.