Granting textual authority to overcome textual tyranny

The point that many religious and political movements take their texts seriously rather than literally has been made by numerous people before. Here, I want to insist on a small addendum, to this point: taking a text less literally can sometimes be accomplished by taking it more seriously. I talk about three different movements- Rabbinic Judaism, academic Marxism, Catholic Christianity and American civic religion and argue that each of them has used a different strategy, but with the same outcome- it’s not just that they take the text seriously but not literally, it’s that the very strategy which lets them take it more seriously also enables them to take it less literally.

That is, I’m going to talk about how religious movements, and similar groups, overcome their holiest texts through veneration. By treating them as supramundane texts, they make the question of what the texts merely appear to say on an ordinary way of reading moot. We’ll find however that the diversity of ways through which they do this matters as much as their unity.

Perhaps a catchier way to put this is to say that they overcome the tyranny of the texts by increasing the authority of the texts. We’ve mostly forgotten about this one weird trick in 2021, because we view taking things seriously as the same as taking things literally. The idea that we can take something seriously without taking it literally might be just imaginable, but the idea that you can go further and avoid taking it literally exactly by a strategy of taking it seriously? That idea is outside how we normally think of things.

I. A lost debate, an aside

When I was in primary school I was briefly in the primary school debating team, (a habit I, fortunately, did not continue in high school). The proposition was given to us- and we had weeks to prepare- That the land of Australia should be returned to its indigenous peoples. We were the affirmative.

We thought this question was impossible for the affirmative. Less than 5% of Australians are indigenous. Handing over governance to such a small minority would be impractical and immoral. The injustices of the past were great, but the egg could not be unscrambled.

Through a very dubious reading of the dictionary entry for the word “returned” we developed roughly the following argument. Australia should be returned to its indigenous peoples in a spiritual sense. We thought this subtle distinction would win us the debate- our opponents would be entirely unprepared.

Our opponents simply ignored our creative redefinition of the question and proceeded to demolish the idea of literally handing over a nation of 20 million people to the control of a minority well less than a million. Meanwhile, we spoke past them completely and spoke glowingly of the need for “spiritual” sovereignty.

We lost the debate deservedly. It was a shit question to give an 11-year-old though. Since then, I have often wondered if there is, in at least some contexts, a way of respecting things “in a spiritual sense” whilst avoiding literal meaning that is not, at heart, infidelity. I still wonder about this. This essay won’t answer this question, but the question does frame it.

II. Interpretation in the context of a tradition, an introduction using Rabbinic Judaism as an example

To reiterate, this is not a general essay on the concept of interpreting a text in a tradition. It is an essay that argues specifically that one strategy to get around difficult texts is to interpret them as so sacred that, paradoxically, what they appear to say matters very little- at least by the standards of a modern reader. However, for those readers without a general background in how texts are interpreted in religious and political traditions, it might be useful to sketch out a broad schematic of how traditions founded on a text work.

The idealized, pure form of what I am talking about is probably best seen in generations of Jewish interpreters. Rabbinic interpretation is an alliance between the living and the dead. The living wan the flexibility to interpret tradition in a way that serves the needs of their community, their view of the good, and their particular theological or political hobbyhorses. The dead want the authority of what they have written to be upheld, and its wisdom to be recognized. The dead possess the authority of generations. The living has a power the dead do not have, they can speak and respond directly to the existing situation.

Thus the living and the dead make a pact. The living will respect the authority of the dead, the source texts, the commentaries, the commentaries on the commentaries. The dead will allow their words (like they have any choice) to be reappropriated to support the agenda of the living.

Orthodox Jews believe in what is called Yeridat ha-dorot, the decline of the generations. Each generation has less authority than the last. On the surface this might seem terribly cruel to the living- are there not wise and good people among them? Yet on reflection, elevating the dead in such a way may be necessary to give them any power at all, for the living have a great power indeed the power of getting the last word in. Or at least the last word for now. Thus to let the dead participate in the conversation at all on anything even like an even footing yeridat ha-dorot may be necessary.

The dead are powerful in authority but rigid, the living are weak in authority but supple. Their alliance is powerful. And it goes on in a cascade. Those now living will soon be dead and the alliance is made again in each generation. Perhaps the knowledge that they will soon be dead motivates the living to treat the dead well, for any callous precedent they establish of ignoring the dead will be applied to them in turn.

As alliances go, it is rather like one from the world of international diplomacy. There are public statements made of mutual respect, but underneath this, there is tension, hopefully constructive. The word “Israel” means “Wrestles with God”. While on the surface, all is smiles, the past is not just something to be let into the present in the way a child might, through a simple interpretation of the text. If, as is often said, the past is another country, strict border controls between past and present are necessary. The text must be wrestled with, slavish application would be nearly as great an error as discarding it altogether.

The text that usually mentioned when explaining the nature of religious authority in Judaism is found in Bava Metzia 59a-b- the famous Oven of Akhnai:

After failing to convince the Rabbis logically, Rabbi Eliezer said to them: If the halakha is in accordance with my opinion, this carob tree will prove it. The carob tree was uprooted from its place one hundred cubits, and some say four hundred cubits. The Rabbis said to him: One does not cite halakhic proof from the carob tree. Rabbi Eliezer then said to them: If the halakha is in accordance with my opinion, the stream will prove it. The water in the stream turned backward and began flowing in the opposite direction. They said to him: One does not cite halakhic proof from a stream.

Rabbi Eliezer then said to them: If the halakha is in accordance with my opinion, the walls of the study hall will prove it. The walls of the study hall leaned inward and began to fall. Rabbi Yehoshua scolded the walls and said to them: If Torah scholars are contending with each other in matters of halakha, what is the nature of your involvement in this dispute? The Gemara relates: The walls did not fall because of the deference due Rabbi Yehoshua, but they did not straighten because of the deference due Rabbi Eliezer, and they still remain leaning.

Rabbi Eliezer then said to them: If the halakha is in accordance with my opinion, Heaven will prove it. A Divine Voice emerged from Heaven and said: Why are you differing with Rabbi Eliezer, as the halakha is in accordance with his opinion in every place that he expresses an opinion?

Rabbi Yehoshua stood on his feet and said: It is written: “It is not in heaven” (Deuteronomy 30:12). The Gemara asks: What is the relevance of the phrase “It is not in heaven” in this context? Rabbi Yirmeya says: Since the Torah was already given at Mount Sinai, we do not regard a Divine Voice, as You already wrote at Mount Sinai, in the Torah: “After a majority to incline” (Exodus 23:2). Since the majority of Rabbis disagreed with Rabbi Eliezer’s opinion, the halakha is not ruled in accordance with his opinion. The Gemara relates: Years after, Rabbi Natan encountered Elijah the prophet and said to him: What did the Holy One, Blessed be He, do at that time, when Rabbi Yehoshua issued his declaration? Elijah said to him: The Holy One, Blessed be He, smiled and said: My children have triumphed over Me; My children have triumphed over Me.

But note -and perhaps I am overstepping my bounds here- that if the law is not in heaven, it is certainly not in the past either. It is here. Obviously, tradition arrives to us from the past but right now, the decisions about how it applies are being made here, on the basis of what people here say. The authority of the tradition must be upheld, the flexibility of present must be upheld, and so it is necessary to wrestle with the law, and with one’s own temptation to rule too leniently out of indulgence, and one’s own temptation to rule too strictly, out of caution.

I have used Judaism as an example, but although none fits the type quite so well, other interpretative traditions in a broadly similar mould exist.

III. The origins, and inversion, of politics

Many, though not all, hunter-gatherer societies are very egalitarian. An anthropologist named Boehm suggests we understand this in terms of counter dominance hierarchies. Here is my gloss on this idea:

These early hunter-gatherer societies weren’t simply passively egalitarian, rather their egalitarianism was an achievement that had to be constantly upheld. The reason that human bands are often egalitarian, whereas great ape bands often aren’t, is that humans developed politics. In its original form, politics was a weapon of counter-power, not power. By allowing coordination by groups of weaker individuals to overcome stronger individuals, politics created early human egalitarianism. Only later was the original use of politics inverted, then it became a tool for an individual to control much larger groups than any alpha chimp or silverback gorilla could have ever dreamed of.

However, per Boehm, politics in hunter-gatherer societies never overcame hierarchy “once and for all”. The tendencies towards hierarchy were always there. Rather, power and counter-power became locked in a struggle of millennia. Powerful individuals tried to consolidate their position, but the group, both consciously and unconsciously, pushed back. The result is that hunter-gatherer societies became riddled with institutions designed to prevent the emergence of powerful individuals and minority factions. These institutions ranged from mocking successful hunters and downplaying their achievements to discrete assassinations of fellows who wouldn’t take the hint.

I am reading David Graeber and David Wengrow’s book “The Dawn of Everything” and that has me fascinated by the cunning and strategy with which ancient societies were able to play this game of power and counter-power. It’s like a game of four-dimensional chess, by correspondence, with time per move allowed on the scale of generations. The struggle to restrain tyranny- tyranny of any kind- is like a subtle and invisible war that pervades history. A common tactic is the decoupling of power and authority. We see power without authority- for example- police officers who were also ceremonial clowns. We also see authority without power- esteemed hero chiefs who are forbidden from actually ordering anyone to do anything and are required to be the poorest people in their village through constantly providing for everyone.

IV. Undermining power with authority

Today we are used to the idea of constitutional monarchs who are not really allowed to do anything. Zoom out a bit though, and it’s quite weird. The idea of a person who, theoretically, is in charge of everything, but in practice, dare not do anything at all, even in some cases appoint their own servants, seems like it should be a very unstable arrangement- like a constitutional crisis waiting to happen. Even should it prove to be stable, it seems like a waste of resources.

Yet historically it is quite common- it is certainly not just an innovation of the modern period. We find long-lived instantiations of this configuration in dark ages France, and in medieval Japan, for example. Moreover, there are often tendencies in this direction, even when they are not fully realized. Many kings and queens throughout history gave up enormous amounts of their power to advisors.

I’m not a historian of monarchy, but I want to hazard a guess as to why this social form might be relatively stable. It resolves the tension between kingly power and kingly authority. In a manner of speaking, authority can be seen as being right in the abstract. Power can be seen as making the decision about what to do. The problem is that these aren’t very compatible in the long run for mortals. When we make a lot of decisions, it quickly becomes obvious that we are not always right. So to preserve the appearance of kingly authority, kingly power is stripped. Thus in some, though admittedly not all, circumstances, precisely as kingly authority reaches a zenith, it becomes necessary for kingly action to come less and less.

But what does it look like to put a text in a similar gilded cage?

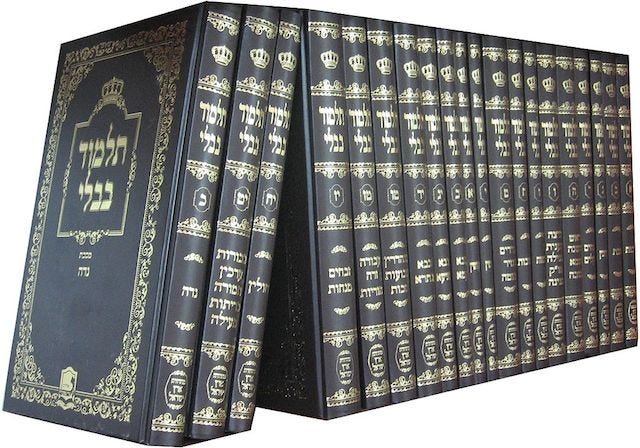

V. Example: Rabbinic Judaism

The method by which Rabbinic Judaism overcomes literalism is through superabundant meaning. The text is laden with so many truths, layers of meaning, and specificities that what appears to be “at first glance” on a literal interpretation may, in fact, not be true or be only partially true. The text is made more authoritative and profound- by emphasizing that nothing in it is accidental and it contains vast meaning- even at the same time as a casual literalism is discarded.

Rabbinic Judaism has a deep respect for the Torah. It is said to have been written before the foundations of the world, according to one source 974 generations before its foundations. It is said to have served as the plan for the design of the world. Despite this (or rather, as we will see in part because of this), rabbinic Judaism is famed and sometimes criticized, for the extremely creative ways it interprets the Torah.

Often the changes are in the direction of humanitarianism. A great example of how the Rabbinic tradition “softens” what the source material apparently says is in the laws concerning the death penalty. The Rabbis end up coming to the conclusion that, in practice, almost no one should ever be put to death under God’s law for almost any reason whatsoever.

And I do not mean “one in a thousand” or even “one in a hundred thousand” I mean almost no one. One Rabbi, R Eleazer even remarked that it is a bloody Sanhedrin that kills a man even once in seventy years (i.e. at all, ever). I won’t go through all the processes by which they reach this conclusion, for they are many, but let me share one example.

In Leviticus 20:9 it is written: “‘Anyone who curses their father or mother is to be put to death. Because they have cursed their father or mother, their blood will be on their own head.

In Deuteronomy 21:18 -21 we get a bit more detail:

“If someone has a stubborn and rebellious son who does not obey his father and mother and will not listen to them when they discipline him, his father and mother shall take hold of him and bring him to the elders at the gate of his town. They shall say to the elders, “This son of ours is stubborn and rebellious. He will not obey us. He is a glutton and a drunkard.” Then all the men of his town are to stone him to death. You must purge the evil from among you. All Israel will hear of it and be afraid.”

The Christian interpretation of this has generally been that a nation under Mosaic law should put rebellious kids to death. Some of them think this reflects a kind of “ideal law” of the old covenant, and is not something that was ever really meant to be put into practice- this would probably be the majority view among theologians. In any case, they hurriedly add, we are under the new covenant, not the old, so it no longer applies. At the other end of the spectrum, some Christian dominionists for example, think that we should literally stone to death a bunch of teenagers. Now, to be fair, many caveats will be insisted upon “the text is talking about really rebellious kids here, we’re not talking about a casual slip of the tongue” etc., etc., but ultimately they do think that at least some teens should be killed for rebellion.

The Jewish approach is quite different. A close and imaginative reading of the text makes the offense so specific that it would never actually apply to anyone. The Encyclopedia Judaica has it:

Interpreting every single word of the biblical text restrictively, the talmudic jurists reduced the practicability of this law to nil. The "son" must be old enough to bear criminal responsibility, that is 13 years of age (see *Penal Law), but must still be a "son" and not a man: as soon as a beard grows ("by which is meant the pubic hair, not that of the face, for the sages spoke euphemistically") he is no longer a "son" but a man (Sanh. 8:1). The period during which he may thus be indicted as a "son" is three months only (Sanh. 69a; Yad, Mamrim 7:6), or, according to another version, not more than six months (TJ, Sanh. 8:1). The term "son" excludes a daughter (Sanh. 8:1; Sif. Deut. 218), though daughters are no less apt to be rebellious (Sanh. 69b–70a).

The offense is composed of two distinct elements: repeated (Sif. loc. cit.) disloyalty and defiance, consisting in repudiating and reviling the parents (Ex. 21:17), and being a "glutton and drunkard." This second element was held to involve the gluttonous eating of meat and drinking of wine (in which sense the same words occur in Prov. 23:20–21), not on a legitimate occasion (Sanh. 8:2), but in the company of loafers and criminals (Sanh. 70b; Yad, Mamrim 7:2) and in a ravenous manner (Yad, Mamrim 7:1). There are detailed provisions about the minimum quantities that must be devoured to qualify for the use of the term (cf. Yad, Mamrim 7:2–3). As no "son" can afford such extravagance, the law requires that he must have stolen money from his father and misappropriated it to buy drinks and food (Sanh. 8:3, 71a; Yad, Mamrim 7:2). "Who does not heed his father and mother" was interpreted as excluding one who does not heed God: thus, eating pork or other prohibited food, being an offense against God, would not qualify as gluttony in defiance of parents (ibid.). But it was also said that one who in his use of the stolen money performed a precept and thus heeded his Father in heaven could not be indicted (TJ, Sanh. 8:2).

As father and mother have to be "defied," to "take hold of him," to "say" to the elders, and to show them "this" is our son, neither of them may be deaf, dumb, blind, lame, or crippled, or else the son cannot be indicted as rebellious (Sanh. 8:4; Sif. Deut. 219). Either of them could condone the offense and withdraw the complaint at any time before conviction (Sif. Deut. 218; Sanh. 88b; TJ, Sanh. 8:6; Yad, Mamrim 7:8). [EDIT BY PHILOSOPHY BEAR: From memory, some commenters say that because the father and mother both have to say it, they must speak exactly the words mentioned in the verses perfectly in unison].

The son had first to be brought before a court of three judges (see *Bet Din) where, when he was convicted, he would be flogged and warned that unless he desisted from his wanton conduct he would be indicted as a rebellious son and liable to be stoned; if he did not desist, he would be brought before a court of 23, including the three judges who had warned him (Sanh. 8:4; 71b; Mid. Tan. to 21:18; Yad, Mamrim 7:7). If he escaped before sentence was passed, and in the meantime his hair had grown, he had to be discharged; but if he escaped after sentence, he would be executed if caught (Sanh. 71b; Yad, Mamrim 7:9).

It is precisely by interpreting every single aspect of the text as of vital importance that they, with respect, in a certain, particular sense, render it meaningless. The exact opposite of how a modern liberal theologian would proceed. Am I saying today’s liberal theologians should go back to this older way of doing things? No, it’s beyond me to have an opinion that, but I do think the alternate ways of doing things are well worth thinking through in detail.

Notice how the analysis goes. It’s difficult to follow translated into English, but a lot of this is coming from placing an overwhelming degree of meaningfulness on every aspect of the text- gender and age indicators, adjectives, quantifiers, etc. etc. What might seem to be the plain meaning of the text is undermined by taking every single aspect of it as entirely serious and non-accidental.

The Rabbis were fully aware that so specified the law was very unlikely to be applicable to anyone in the whole history of the world. The conclusion they reached was that this law was included as a warning about how serious problems can get if they are left to fester. Thus the text is transformed into allegory, but not in the usual way that is done in our era- by treating the text as below the level of literal meaning, rather the text is elevated by ascending through higher and higher degrees of literalness.

It’s not just about the law either. A literal reading of the story of King David, taking its “plain meaning” would suggest that he:

Betrayed the nation of Israel and fought for its enemies. Indeed, with eagerness.

Committed adultery (and possibly rape as there is no indication given that Bethsheba returned his affections)

Stole a man’s wife

Killed that man

In other words, he comes across as a wicked brute who was, for unclear reasons, nonetheless favored by God.

The Rabbinic tradition, through a combination of very inventive and close readings of the text and supplementations of the available material, holds that Davids's sins in this and other matters were extremely minor. He did not actually commit the sins that he seems to commit in the story. Indeed the Rabbis state “whoever said David sinned is surely in error (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 56a).

This process of interpretation may seem sad to our eyes if we are enraptured of the picture of David as a broken sinner who nonetheless received God’s grace. However, there is actually something humane about interpreting David not as a brutish thug. For if David is a brutish thug who is nonetheless beloved by God, it follows that we have no right to judge a king for his actions, because he, like David, might be beloved anyway. By insisting that David was good, they implicitly bound future kings to be like David.

A friend told me once that there’s a Christian congressional bible study that tells the representatives and senators to think of themselves as like King David. Just like he did, they sin grievously, but ultimately God loves them because God chose them for his purposes. Just like king David, their personal indiscretions, regrettable as they may be, are beside the point. Perhaps this brings home how terrifying it could be to have a senator who thinks God wouldn’t be all that fussed if they killed a man to marry his wife- they could still be God’s favorite.

I have no idea whether any of that about the congressional bible study is true, but I can certainly imagine a wicked king comforting himself with the thought that he was like David. Perhaps then the Rabbis were wise indeed to insist the story is not what it seems. At any rate, a reduction in literalism doesn’t just coexist with an increase in authority- rather the increase in authority necessitates the reduction in literalism.

VI. Example: Marxism

The method by which a certain strain of Marxism overcomes literalism via veneration is through conceptual abstraction. The point of the text isn’t the concrete claims, it’s the brilliant subtleties in the relations between ideas, the way of their unfolding, and also the method by which they are arrived at. The book is portrayed as more brilliant -capturing layer after layer of human relations- at the same time as a surface literalism is denigrated.

Within the Marxist tradition there are many approaches to the classical texts. I think probably the three pure “types” are:

The 1930’s Marxist sect approach: A mechanical Marxist literalism about everything Marx (and Engels, and Lenin) say, treating it as a series of more or less quantitative laws etc.

The sane approach: An attitude that treats Marx as a useful thinker who’s sometimes right and sometimes wrong, and denies the validity of a straight-up “appeal to Marx” to prove anything

The academic approach: A quasi Hegelian Marxist mysticism that takes him as saying something very profound, but not in the first instance, mundane statements about anything so plebian as actual specific quantifiable things. Rather he’s engaged in a profound kind of dialectic, to which what appear to be the specifics he’s talking about are dispensable.

I would say that my own approach to Marx is 60% the sane approach, 25% the academic approach and 15% the Marxist sect approach. Mostly I think of him as just the best among the social theorists. Sometimes though I get the sense that he has a special way of seeing and thus I buy a little bit into the academic approach. Sometimes, often in the context of polemics, I find it useful to frame things in terms of the mechanical approach. The mechanical approach is ultimately an oversimplification, but it can be useful to shock someone into another way of seeing.

But for our purposes, the reason I present this trichotomy is to draw attention to approach 3. It’s a playing out of the pattern- burying texts by praising them. Don’t be so finicky, don’t miss the forest for the trees, It almost would be an insult to the text to be so very jejune as to to worry overmuch about whether the formulas it presents for determining value etc. are quantitatively accurate. Don’t you know that it’s a critique of political economy, not just another work of political economy in its own right? The degree to which these interpretations of Marx conform to what Marx actually thought isn’t our concern here. Rather our concern is that these arguments let the theorist get out of having to defend or attack Marx on these points not by diminishing the authority of the text, rather the opposite, by making it above such mundanities as what it appears to say at its face. The method is very different to Rabbinic Judaism- a focus on conceptual abstraction- both of methodology and content- more than a superabundance of meaning. Despite these differences, the result is similar, the text is made to have greater authority by the same intellectual maneuver that makes the literal meaning matter less.

VII. Example: Catholic Christianity

The method by which Catholicism overcomes literalism via veneration is through salvific contextualism. The bible is holy because it is part of God’s holy plan for the salvation of humanity. As part of an infinitely subtle plan, it would be a mistake to see it as a go-to “grab bag” of readily available truths. The book is made more holy (through integration into an incredible cosmic plan) at the same time as it is made less literal.

Catholics believe that the bible is infallible in moral matters, and matters essential for salvation (though not on most matters of empirical fact):

“The books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation.”

Nonetheless, Catholics will tell you that the bible, on its own, can’t be read as a guide to doctrine. Catholics will generally cheerfully admit that by reading the bible alone earnestly, you could arrive at a form of Protestantism, but they will continue that, reading the bible earnestly you could arrive at almost anything. Thus, maybe, sincere individual reading isn’t up to the task.

It may be instructive consider what has generally happened to Christians who insist that the bible alone should structure Christian faith. There are at least 200 protestant denominations in the United States- and this is a conservative estimate.

The Protestant conceit, say Catholics that we’re each meant to pick up this book, well over three quarters of the way to a million words, and each study it as if for some private final theological exam by the Lord God is gives the Lord no credit, as if in his providence he forgot to provide teaching for us. Trying to read it alone for the purpose of finding salvation is a bit like setting out to cross the Atlantic in a rowboat. What kind of cruel God would setup up a 700,000 word puzzle box, and only if you get the right answer do you get to go to heaven?

As a result, many Catholics will say- only half jokingly- that you shouldn’t really be reading the bible alone unless you have a theological degree. “Only priests, rabbis and experienced monks and nuns and scholars should be permitted to read the bible” said one Catholic I follow on Twitter.

Sometimes individual Catholics will- more out of a little irreverent humor that theological conviction- disparage the bible when making this case.

There’s a kind of riposte that you can make to this line of reasoning. Take some set of Catholic beliefs that can’t really be found in the scriptures, say the perpetual virginity of Mary. The problem is not that just that it isn’t obvious in the text- that could be dealt with easily. No, the problem is that the perpetual virginity of Mary is apparently contradicted by the text. You can make a pretty good scriptural case against it using many bible verses like:

Isn't this the carpenter? Isn't this Mary's son and the brother of James, Joseph, Judas and Simon? Aren't his sisters here with us?' Mark 6:3

Of course you can dispute this. You can claim, as do many Catholics, that the word translated here “brother” can also mean “cousin” in ancient Greek. I am told scholars of ancient Greek generally do not find this persuasive. Or you can go the Eastern orthodox route and say that these were children of Joseph by a previous marriage. I’m sure there are other possible lines of argument too. Who knows, maybe one of them is right, but even if they are, that still leaves the question why did the Lord God choose to make his book so misleading on matters of doctrine? Leaving things out would be one thing, but including things that, on a superficial reading, contradict his holy church seems like something God wouldn’t do.

Monsignor Bransfield has an interesting response to some related concerns to this, that I think exemplifies some of the moves any Catholic is going to have to play:

Some beliefs are more hidden. Love loves to hide secrets, so that when we find them we are enraptured even more by their beauty. The mystery of Jesus is so profound that sometimes you have to look closely to see all the parts that he has made known. The Holy Spirit has hidden some dimensions of the mission of Jesus in the Bible. The truths of faith are clarified by the Tradition through the Magisterium, the Church’s authentic teaching office. These truths never contradict the Word of God in Scripture, but serve to articulate its truth more clearly.

What Mongsignor Bransfield has begun to do here is conceptualize the bible as something other than a document containing a collection of things you should believe. The bible isn’t meant to be a succinct declaration of good teaching, it’s meant to be a challenging document that serves many different purposes for many different audiences. In parts at least it is meant to be confusing.

The reasoning makes at least some sense. God is omniscient and infinitely intelligent. He anticipated every single person who would ever read the bible and what their response to it would be, over thousands of years of history. For those billions of people he had billions of purposes, to teach yes, but also to chastise, improve, test, inspire awe and humiliate. It is an infinitely planned document.

And for exactly that reason, you can’t just pick it up, grab the most natural meaning that occurs to you, and read that as true doctrine. The process is perhaps most similar to the Jewish case, though the emphasis is a little different, one focuses on deepening the text whereas the other focuses on expanding the links between the text and a broader salvific context.

Once again, the very sacredness of the document becomes a reason you can’t take what it appears to say too seriously. Once again, meaning is trapped behind a gilded cage of respect. I’m not saying the thought process isn’t justified, but that’s the result.

VIII. Example: American secular religion and the constitution

The method by which the American Civic religion venerates its holy book- the constitution- while at the same time evading literalism about it might be called synecdocheism. The text is transformed from a text into a symbol meaning something like “the wisdom of our founding sages”. As the text is no longer primarily a text, but a holy symbol, it simultaneously becomes more divine even as its literal meaning fades.

The American constitution, interpreted literally and by original intent, suits the interests of no one in America except maybe a very particular type of libertarian (and even then…). Liberals, to their credit, at least acknowledge this implicitly with their “living constitution” theory, that the constitution develops over time, although conservatives respond, not implausibly, that this is just a form of Kritarchy. The conservatives haven’t really got an alternative though.

Despite disagreeing with much of it, all patriotic Americans love their constitution. Let’s review some contradictions:

While the practice of keeping an enormous long term standard army is probably legal in the letter of the constitution, it is at least very arguably against the spirit of it: The Congress shall have Power To . . . raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years, Yet that doesn’t bother anyone very much.

Even those who defend the electoral college, seem to have very little interest in implementing the electoral college as it was intended- a body of educated men appointed by the states who have a discussion with each other and choose who should be president.

A literal reading of the constitution has no place for the qualified immunity doctrine, yet while both liberal justices and conservative justices have hemmed and hawed about it, they haven’t gotten rid of it. It looks possible that for the right case the supreme court justices might be willing to substantially reform it, but, constitution or no, they’re unlikely to just drop it. Outside of the courts a majority of conservatives, the faction which loves the constitution the most, oppose eliminating qualified immunity because support for qualified immunity has become coded as a pro-police issue.

Judges balance the plain meaning of the text against their policy preferences, and an assessment of what they think they can get away with. Whether conservative or liberal, they always have and they always will.

Yet despite Americans not taking the constitution literally, except where it suits them, they certainly take it seriously. There’s a great Onion article entitled “Area man passionate defender of what he imagines constitution to be”. American passion about the constitution isn’t weakened by their loose regard for what it actually says, American constitutional veneration is enabled by this loose regard. It has (at least partially) moved from being a document that says specific things, which one might agree with or disagree with, to being a synecdoche of all things that are good in American life. Though they have used a very different method to the Jewish tradition’s relation to the Torah, the Marxist relation to Capital or the Catholic relation to the bible, they have come to a similar result. They venerate the constitution not in spite of, but by means of, the very same process through which its specific meaning becomes secondary.

The only difference is that the process is a lot simpler here. To the extent it is thought about at all, it goes like this, taking the example of qualified immunity.

Axiom: Constitution=Good

Axiom: Pro Police=Good

Lemma: Constitution=Pro police

Axiom: Qualified immunity=Pro police

Theorem: Qualified immunity=Constitution

Americans avoid the literal meaning in a very different way, they almost don’t think about the meaning at all except where it suits them. Rather they transform the text into a symbol. Because it is a symbol, not a text, it almost doesn’t have a meaning anymore- at least not in the way texts have meanings. The result is that, again, veneration reduces literalism.

Sorry, I'm just not convinced. It seems very clear to me that in all these groups, there is a clear gap between what the book actually says and what those who venerate it would like it to say, and these are all too-clever-by-half means of trying to close that gap. They aren't taking it "more seriously" than the literalists; they are just trying desperately to take it seriously while disagreeing with what it actually says.

The one and only obvious solution that would truly solve the problem is the one that is simply unthinkable to them: ADMIT THE BOOK IS WRONG.

How did it take me so long to find this? Fascinating stuff!