Expressions of hatred of LGBTQ people are common now. For example, see this tweet:

“An ugly protest today. A mob of self-described “Christian Fascists” tried to force their way into a gay establishment in the gayborhood of Dallas holding a family event while chanting “Groomers””.

And we see these sorts of statements from fairly prominent figures on the right:

This sort of thing is alarming enough on its own but it particularly alarms me in view of the rising number of monkeypox cases. If cases get into the hundreds of thousands globally, enough to force serious public health precautions, the right will surely take a portion of it’s fury out on the LGBTQ community, who they will call plague bearers and typhoid Mary’s.

So the question is, could things get really awful on this front? I’m talking about recriminalizing homosexuality or “cross-dressing” levels of cruelty. Public lynching levels of fascism.

I’m caught between two impulses.

The first is to dismiss talk of a crisis or rupture on two grounds. The simplest ground is that such predictions are usually false. The more complex ground is that obsession with a moment where things get “really bad” elides something more immediate. Focus on the apocalypse and you will forget that the world is always ending for someone. By wondering if things will fall apart, you normalize our world and limit your imagination to clinging to it. Fancy that you say! The United States where 1% of the population is incarcerated might be ‘near crisis’? It’s apocalypse now, cherub.

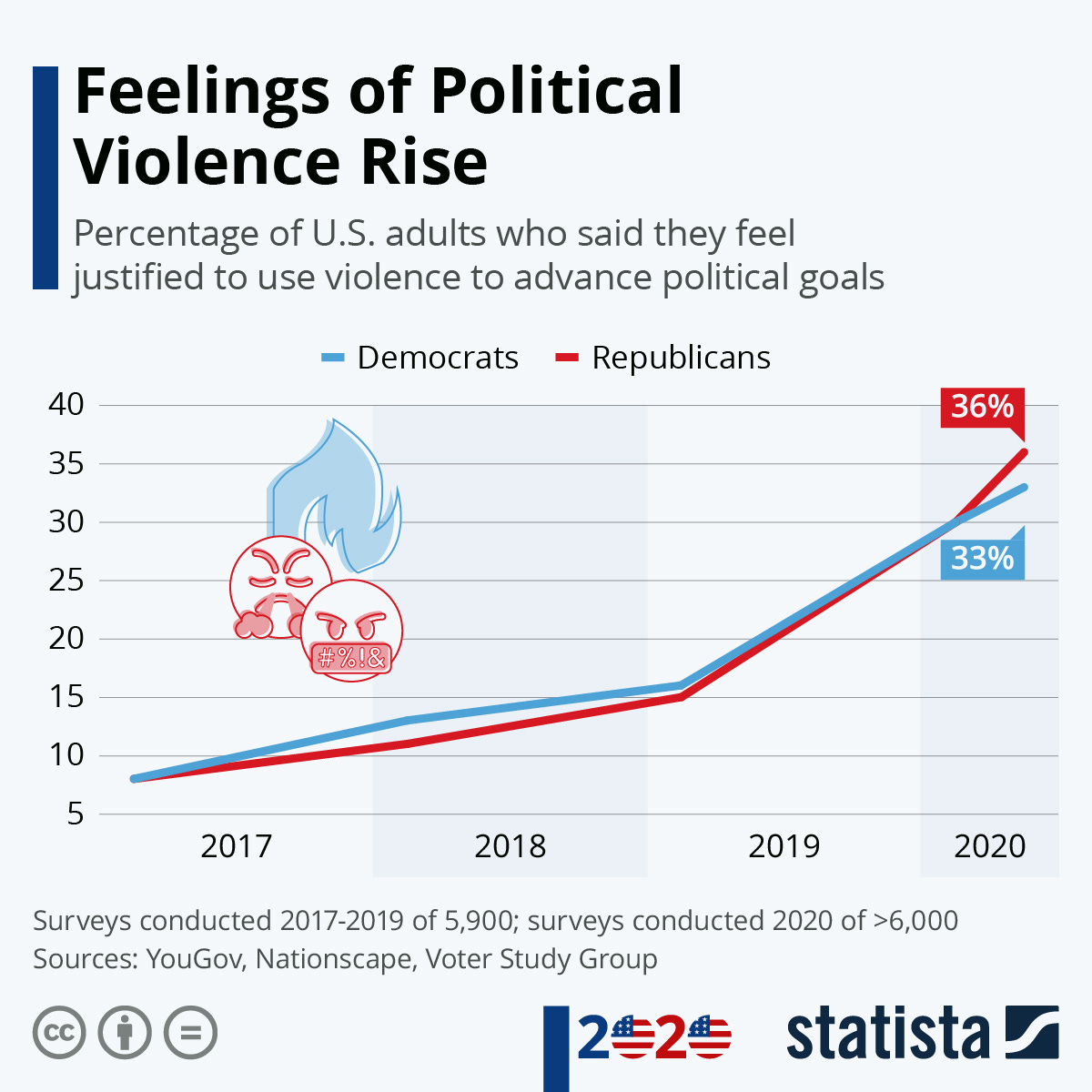

The second contrary impulse, the doomer impulse, notes that it’s foolish to dismiss the warning signs of social decline just because people have been yelling about them for six years or so. Weimar Germany lasted a decade and a half, after all. The ante has been upped repeatedly and there are no clear signs of stabilisation. Something is happening:

And yes, there are things in this world worse than America’s current kleptocratic liberal decadence.

The upshot is that I’m not sure whether America is on the edge of something horrible -perhaps targeted at LGBTQ people- or not. When you’re not sure though, plan for the worst. So let’s think about a worst-case scenario and how we might act with effectiveness and grace in it. I think it’s a good idea to think about these cross-road moments with a kind of zoom-out. What to do if you think you might be under the eyes of history? If you’re concerned that you might be in the sort of situation where, thirty years from now, people will be discussing why people like you made the choices they did?

There are a lot of strategic questions here, but I want to focus on the fundamentals. In theory, it’s hard to get these fundamentals wrong, yet in practice, many will forget them.

How to behave if you might be living on the eve of a political crisis

Think about the perspective of history. History isn’t going to be kind to excuses like “but they were so irritating”, “but they were really cringe”, “I was only supporting the villains ironically”, and “I was a moderate supporter of the villains”. Make your choice on the basis of fundamental principles, not contingencies and accidents.

Make your position clear. Say openly and publicly that you support all those at risk. Even if it’s cringe. Even if you think it shouldn’t have to be said. Be particularly clear about those who are regarded as the most “difficult” cases, the ones “moderates” might want to sacrifice, especially trans people who are right now being targeted with exterminationist rhetoric. Edit: Another group that seems to be under special attack right now: the homeless.

Focus on being a clear, authoritative, knowledgeable yet humane voice on events and politics to your circles. Your circles include work, buddies, old buddies, and internet friends. Talk about this stuff on Facebook, it’s less of an echo chamber than Twitter. Most of all, talk about it offline.

Don’t turn anyone away who wants to join your side, or leave the other side. Try to have a clear political voice, but don’t expect such clarity from your fellow travelers, let alone send them away if they don’t display it. Encourage baby steps in your direction. Don’t punish people who are displaying sympathy for your cause by hectoring them. It’s more important to win than it is to dispense justice for others’ perceived sins.

The first key to persuading is listening, really listening, to what the other person has to say. find common ground and walk that common ground with them to lead them towards your position. The second key is really knowing your stuff.

Organize. Unions, community groups and electoral groups.

I’ve written a guide to persuasion in my book, and I’ve reproduced it as an appendix here.

Appendix: thinking about political persuasion from a left-Wing point of view

1. The American left cannot win without persuading large swathes of the right & center

There’s a comforting lie that some parts of the American left like to tell themselves. We don’t need to worry about convincing conservatives—we just need to get non-voters to vote. This has never rung true to me. What evidence we have suggests turnout is not a panacea. For example, culturally the UK and Australia are very similar, however, Australia has compulsory voting. The political center of the UK and Australia is more or less the same despite this difference.

The evidence from the US suggests that non-voters in the US aren’t as politically different from voters as is sometimes claimed. As of the time of writing, 53.5% of registered voters disapproved of Trump whereas when we look at polls of all adults… thefigure is exactly the same—53.5%. Registered voters are more likely to approve of Trump than adults in general, but only very marginally (42.3% v 40.7%).

The Democrats would win if everyone turned out, but not by all that much. Specifically progressive and left-wing Democrats, even on the most generous conception of these, would still be a long way from a majority. Thus there are strong reasons to think the left can’t win simply by getting more people who share their values to turnout.

Anti-parliamentarianism won’t save you either—it’s very hard to win a revolution if 75% of the population, at least, disagree with you. The idea that no persuasion beyond a little bit of base motivation is necessary is a comforting myth—a way of telling ourselves we don’t have to talk with those self-satisfied, self-centred, self-serving, deliberately ignorant idiots over there.

There’s a natural tendency to view those who disagree with us on topics which are genuinely important as abhorrent. In turn, abhorrent things are viewed as dirty, or likely to contaminate us. I’m not going to argue about whether these feelings are justified, instead let us just say they aren’t useful—they’re not workable levers for changing the world. If you pick a random person on the street it’s almost certain that they’ll hold extremely dangerous and regressive political views on at least one topic. I’m not talking about minor issues here—I’m talking about big things like war, criminal justice, etc. Despite that, it is absolutely essential that those who can engage with people and try to persuade them do so.

TLDR: examples from overseas, and data from the US itself, indicate that increasing turnout or motivating the base alone will not win the US for the left. There will be no left victory in the United States without persuading a lot of conservatives and centrists. In the rest of this piece we’ll go through the permutations and methods of persuasion from a left-wing point of view.

2. Arguing the line

The kind of persuasion that we are probably most familiar with is what I call arguing the line. Arguing the line is, quite simply, arguing vigorously for your position. Sometimes this is done against a real interlocutor, as in a comment or Twitter thread, and sometimes this is done against a purely hypothetical interlocutor, as in many blog posts. Arguing the line is not a collaborative process, it is a confrontational process, although it is not necessarily cruel or angry.

Some would say that this is the least effective of persuasive strategies; I disagree, although it is often overplayed. In order to see how arguing the line can be effective, it’s important to understand what it will generally not achieve.

Usually, arguing the line is not going to change the position of the person you are arguing with on the spot, especially if the argument is happening on the internet. If it does change anyone’s position immediately, it will almost invariably be on small points. Rather than changing the mind of the person you are arguing with, the primary purpose of arguing the line is to convince onlookers. There are a lot of people with relatively unformed political views floating around in pretty much every space on the internet. If you’re on the fence, seeing someone argue coherently, reasonably and powerfully for a position like Medicare for all or an end to foreign interventions can have a big impact.

Keeping in mind your real audience—undecided observers rather than your direct interlocutor— clarifies the mind. It will help you pick your battles, keep your morale up, and refine your methods and pitch. This isn’t to say you should just speak as if your direct interlocutor weren’t there or isn’t worth paying attention to—in most contexts this would make you seem weird, rude or aloof.

3. Rules of thumb for arguing the line

You should aspire to state your arguments so clearly that no one can misinterpret you even if they want to. This is because it is quite likely your opponent will be deliberately or quasi-deliberately trying to misinterpret you. You almost certainly won’t succeed in making your work impossible to misinterpret, but it’s important to try and get as close as possible. This is because if you’re engaged in a back and forth with someone, onlookers will only be partially paying attention. Thus if your opponent attributes a meaning to you, many onlookers will automatically assume their interpretation is correct unless you have been so totally clear that even people who are only half paying attention can see that your opponent is bullshitting.

Often people’s impression of the epistemic virtues of the debaters stays with them longer than their recollection of the actual arguments (e.g., “This person seemed reasonable” vs “This side seemed histrionic or dishonest.) Thus, without seeming like a pretentious dickhead, make your epistemic virtues visible. Show others that you are measured, calm, inquisitive, nuanced where nuance is appropriate, perspicuous and attentive to the whole picture. If you aren’t already these things—try to be! If you can write or speak well, do so.

A good rule is that you should avoid engaging where you are clearly going to get stomped. This includes topics where you have no idea what you are talking about and circumstances where your opponent can control the flow of the conversation in such a way that they can cut you off at leisure. There’s an old proverb about this, it’s harsh but it makes its point: It is better to remain silent and be suspected of being a fool than to open your mouth and remove all doubt. The point being that if you don’t say something your side will be perceived as having lost ground, but not as much ground as if your opponent can smash through a tissue thin defence.

Consider the way Ben Shapiro bolsters the rhetorical strength of his case by picking dissenting audience members currently under the grip of strong emotions, controlling the flow of conversation and “destroying” them. This is a great example of why it is sometimes better not to engage if you can’t do so on fair (or better than fair) terms.

The above rule has to be tempered with the recognition that there is sometimes value in being the lone dissenter. If you are the lone dissenter, you’re certainly going to ‘lose’ the debate, since the numbers of the other side mean they will get more speaking time—they can ‘rebut’ all your points and put forward more ideas than you can reply to. Nonetheless, there can be value in clearly, simply and powerfully stating your ideas. In the Asch conformity experiments—for example—suggested that a group consensus about something has an extremely powerful effect on onlookers, but even a single dissenter can greatly weaken the effect of that conformity. We can think of this as the principle of contested space—if there is a space, conceptual or physical, which the left is not contesting to at least some degree then there is a problem. (Incidentally, fuck the left-wing purists who will have a go at you for entering, participating in and contesting non-leftwing spaces, they’re among the very worst the left has to offer. Which is not, of course, to say that you should be posting on fascist boards)

People—even fellow travellers—always try to pigeonhole arguments into being a variant of something they’ve already read—either to dismiss it or accept it without thinking too deeply. People are always looking to be able to say “oh this writer is one of X type people so she thinks Y&Z and must be vulnerable to objection P”. In order to avoid this, try throwing in curve-balls that will surprise your readers expectations of what they think you believe. For example, taking a somewhat trite example and channelling the Communist Manifesto for a moment:

“I’m a Marxist so I believe that capitalism has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals; it has conducted expeditions that put in the shade all former Exoduses of nations and crusades.”

4. Rogerian persuasion

If you want to actually persuade an individual of something, and not just onlookers, Rogerian persuasion (named after the psychologist Carl Rogers) is your best bet. Most people don’t have especially clear or fixed views on issues, but instead have a mixture of beliefs and values related to any given topic. The idea of Rogerian persuasion is that if you want to persuade someone on any given topic, you should focus on areas of shared and similar beliefs and values. You want to demonstrate how those beliefs and values might actually support a left-wing position on the topic. This is easier and less artificial than it sounds, because most people at base have many quite left-wing intuitions and beliefs, they just get crusted over by reactionary propoganda.

Focus on demonstrating that you understand what the other person is thinking and saying. A good technique to combine Rogerian persuasion is what counselors refer to as mirroring. Paraphrase key things the other person has said and repeat it back to them to show you understand and check that you are on the same page. One very important point in Rogerian persuasion is never to leave the other person in a position where they don’t have an out. You want them to have a natural route of escape. A way they can walk back from positions and change their mind without making a big mea culpa. People usually aren’t that afraid of changing their minds, what they care about is the humiliation of having to admit that they were previously wrong, especially if it is in a way they now recognise is a bit repugnant. As a result, people often want to dress up a big change of heart as simply stating something they’ve always believed ‘more clearly’ or ‘clarifying’ their views.

There’s a fine line here. I’m not sanctioning dishonesty, and there probably are times when people should feel a little bit uncomfortable. But remember, this isn’t about ‘winning’, much less about punishing the person for their prior views. It’s about the transformation of the world.

Don’t try to turn Rogerian persuasion into passive-aggressive hippie focus-group bullshit where you get exactly the cookie-cutter result you want. You really do have to listen, you really do have to actually care what the other person thinks and accept—at least in the context of that conversation—the differences in your opinion. Above all you have to respect the autonomy of the other person. This respect for what the other person thinks means that you’re not going to turn out intellectual clones of yourself, but that’s okay.

Sometimes you’ve got to accept partial wins. For example, if you can persuade someone who supports the death penalty, to restrict that support to a much smaller set of circumstances, that’s a win. If you can persuade someone to move from supporting the criminalisation of abortion to just being personally opposed, that’s a win. Accepting these partial wins does not mean having to compromise your own views.

5. Mere presence

In a lot of ways, this is related to Rogerian persuasion, but it’s worth emphasising separately. Simply being a part of someone’s life while holding left-wing views can exercise a powerful influence. Just letting others know that, for example, you support free public college tuition has an effect. You are giving the other person information—that it’s possible to be a reasonable, kind person and believe these ideas. For a lot of people exposed to an intense diet of right-wing memetics this is a powerful thing, since their understanding of the world includes the assumption that it’s only weirdos who think those things. Try letting people know you’re left-wing, being a presence in their lives, but also being cool about it.

6. Don’t forget the Socratic Method

Socratic questioning is a kind of arguing by question, where rather than concentrating on putting forward propositions of your own, you focus on asking difficult questions about what the other person believes. In the ideal case (as Socrates practiced it) Socratic questioning leads the other person to move to your own position, as they struggle to deal with the difficulties you raise by amending their position step by step. Even if you don’t get that far, Socratic questioning is a powerful method. Socratic questioning can complement either Rogerian persuasion or arguing the line, although the kind of Socratic questioning that works best will vary depending on your purpose.

Intuitively it can look like the person asking the questions is less powerful than the one giving the answers. It’s the person answering the questions who gets to describe their worldview, and who speaks the most. This is an illusion however; there is immense dialectical power in asking the questions. When someone is simply expounding their view they can make big logical leaps which are all to easily concealed from the casual reader. Under questioning though, this stuff comes out. You can really expose the underlying assumptions.

Here’s a great example of what Socratic questioning can look like, owing to Current Affairs magazine podcast: “Single payer can work in places like Sweden because they are more homogenous, the United States is too diverse for single-payer healthcare. “Okay, Canada is only a bit less diverse than the US. What do you see as the key differences between diversity in the United States, and diversity in Canada, which makes single-payer possible in Canada but impossible in the United States?”

The question sounds very innocuous, but is actually quite difficult to answer without either A) implausibly insisting that the relatively small quantitative difference in diversity levels makes a huge difference. B) Saying that the problem is the kind of ethnic groups the US has—straying dangerously close to explicit racism or C) Just outright changing the topic.

7. Make propaganda

I don’t have much to say about this except an exhortation: Make and distribute stuff that can persuade people: memes, posters, pamphlets, wearables, comics, drawings and essays.

The majority of internet users (as around 99%) are largely passive. Outside the internet, the ratio of culture consumers to culture producers is even higher. You really don’t have to try very hard to have an out-sized impact (hundreds of times that of the average person) on the conversation. Look at what other people are doing who are good at making persuasive political materials, study their technique, experiment and, hey presto, you’ll almost certainly find there’s at least one medium where you can excel.

8. Organising as persuasion

It’s a pretty well-known observation that the process of fighting for justice is radicalising. Thus if you want to persuade people to the left, you should start organising. The reasons being part of organising tends to draw people to the left are many, but include:

A) The support they will (hopefully) receive from the leftists.

B) The conversations they will have with other people they are organising with, and the shared concerns and experiences they find together.

C) The opposition they will face from capital and the capitalist state.

There are limits here. For example, around the world numerous farmers have been organised to oppose fracking on their land. While this experience has no doubt moved the campaigning farmers to the left in some ways, in many places the majority of these farmers will still vote for centre-right parties. The limits are, based both on the objectives of the campaign, and the class and social position of those participating. Nonetheless, organising changes people.

9. Institutions as persuasion

Left-wing institutions are the useful residual of concrete left wing struggles and organising. For example, many unions can trace their existence, however distantly, to a particular wildcat strike. Unions are the ultimate example, but not the only one, even within the sphere of industrial issues. For example, although they are rare in this period, it was common in the past to have worker’s education institutions, workers schools etc. Most of these can trace their origin to some particular flare-up in the worker’s struggle. The same is true of women’s libraries, associations of racial minorities, pride marches, even the much maligned student union. These institutions often owe their existence to big moments in particular fights, and while the struggle continues, they often outlive the specific campaigns or moments of intense action that gave birth to them.

I’m including them in this guide because these organisations perform persuasion on an industrial scale, they aim to align not just individuals, but whole demographics and suburbs to a cause. Their strategy is a form of persuasion, but it transcends persuasion, when successful they create whole new political categories and identities.

One of the major problems with sectarian organisations is their tendency to take for granted these kinds of institutions and not recognise their value except as a momentary tool of the sect. Inversely though, it would be a mistake to regard these organisations as inevitably radical—they tend to become liberal over time when disconnected from struggle. Too much faith in these organisations is linked to that common new-left disease, the tendency to venerate oppressed communities without recognising the contradictions that exist within such communities.

10. A word on critical thinking and informal fallacies

Many Universities have courses on critical thinking. In a good critical thinking course one learns about formal and informal fallacies, cognitive biases, the scientific method, the basics of probabilistic reasoning sometimes up to Bayes’ theorem, a tiny bit of formal logic, maybe a smidgen of inferential statistics, and a few other useful tidbits. A lot of this material, but especially the study of informal fallacies has been given a bad name by poorly socialised people who try to use it like incantations from Harry Potter (“Ad Hominem!”,”Petitio principii!”) and don’t pay attention to the larger conversational context. Fragments of reasoning that would be fallacies in one context are perfectly valid in other contexts. Sometimes arguments that appear to contain informal or formal fallacies are just abbreviated statements of perfectly fine arguments. My advice would be to familiarise yourself with ideas like informal fallacies, cognitive biases, probabilistic reasoning etc. but generally don’t use the words and terms in your explanations of your thinking. Instead explain the basic flaw in your opponent’s reasoning without appealing to the jargon of cognitive biases or informal fallacies.

There’s two good reasons for this. The first good reason is that you should be avoiding jargon generally. The second is that you’ll avoid the bad reputation that these particular conversational manoeuvres suffer. Specifically with regards to ad hominem attacks directed against yourself, either ignore them, or, if you must, retaliate with a similar insult or comeback. Pretty much everyone understands that ad hominem quips don’t really prove anyone right or wrong. Complaining that your opponent’s insults are fallacious won’t do you any favours and just comes across as whining.

11. Dealing with bad faith

A lot of people don’t want to engage in persuasion because inevitably many of those who wish to discuss politics are acting in bad faith. This is a serious problem, the only advice I have is try to make careful and reflective judgement calls on when discussion is worth your time.

For example, there’s little point arguing with someone who clearly isn’t willing to listen if there isn’t an audience of potentially undecided people to see your argument (although, since the majority of posting is done by a small minority of people, the probability of you having an audience is usually higher than you think.)

In general, beware time wasters, but recognise that on occasion time wasters will successfully waste your time, and this probably can’t be helped. The far-right are a special case. Arguing with the far-right has many dangers and few benefits. For example, some ideas are so niche that they gain relatively more oxygen if you argue with them even if you completely squash it. Let’s say someone comes up with some novel far-right position or titbit and you completely squash it. Good for you, except no one had even heard of it before you bothered so no matter how thoroughly you squashed it, you’ve now helped it enter the discourse.

There’s a special kind of bad faith associated with far-right argumentation. As Sartre puts it in relation to anti-Semites:

“Never believe that anti-Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti-Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert. If you press them too closely, they will abruptly fall silent, loftily indicating by some phrase that the time for argument is past.’

In other words, if your opponent has bought into the asetheticisation and/or gamification of politics, and cares not whether they are right or wrong—but only for power—why bother? Prove their thesis that their ideas will give them more power wrong in practice, by usefully spending your time elsewhere. The only thing I would caution here is that you shouldn’t use not talking to the far right as an excuse. There’s a sense for example in which what the typical Trump supporter believes is far-right by many reasonable standards. However, applying such a definition in an American context simply wouldn’t be useful. If you’re not comfortable talking to Trump supporters personally, fine, but don’t make a principle out of it.

Maybe I’m being obtuse here, but isn’t polarization the problem? If that the case, how will “persuade people to join our side” really fix the problem?

Is the idea that if enough people join the left, somehow the right will just… stop existing?

Are you not curious about why things seem to be heading in a negative direction? You mention Weimar - why did things explode there? Surely an understanding of the specific root causes of polarisaztion and destabilisation will help you to prepare for its specific consequences.