Notes on punishment

I like to write notes from time to time capturing my views on different subjects

Punishment considered: Although I don’t support vigilante justice, I’ve always felt infinitely more sympathetic to rape victims who kill their attackers than to people who call for a crueler justice system. Someone who kills the one who wrongs them doesn’t harm someone who is under their power, whereas, the state, when it is harsh or cruel, does so. This should disturb us, even as it is unavoidable in some cases. Punishment by the state is close in its moral character to torture because it inflicts pain on a defenseless subject. It is sometimes necessary, but we must never forget this frightening nearness.

The original sin of humanity is witchhunting. Many human societies throughout history have believed that there was no such thing as natural death or even natural misfortune. These societies saw all non-violent deaths and sometimes even simple bad luck as originating in witchcraft carried out by specific villainous individuals. In the witch-hunt, we see a refusal to understand that the causes of strife are larger than ill will. We see an insistence that problems only arise because individuals have chosen to do the wrong thing. “Witchcraft” serves as a cognitive emblem that lets us avoid thoughts like “maybe that old woman is a bit odd because we’ve isolated her and let her grow poor”. “Maybe the crops failed because that just happens sometimes”, “Maybe strife is raging in the village because we haven’t thought about the equitable division of land”. All the complexities of the world are squished. All considerations of larger social and natural structures are squashed. The enemy must be an individual person motivated by ill will and not a larger arrangement of society, or an aspect of the natural world. Once we kill the enemy, everything will be okay. The solution is punishment, the more final the better. In this sense, the witch burning is the original sin of humanity and the perfection of the (il)logic of addiction to punishment. The fetishistic sense is that we can avoid changing the way things work, or even thinking about the way things work if only we hurt the bad people. That the world is just except when bad people wantonly choose to be bad. Punishment, when it becomes an addiction, lets us sustain these illusions, and is not unlike drinking to avoid unwanted thoughts- that maybe the problems are larger, deeper, harder.

Sadness and anger: I’ve read many legal judgments in criminal cases in my life. The best-articulated judgments, it seems to me, are not unfeeling, nor full of bile, but filled with sorrow that someone would do this.

We often feel anger at those who have wronged us because we do not wish to allow ourselves to feel sad, but sadness is no terrible thing, especially in comparison to rage. Sadness is not weakness nor is sadness necessarily passive. Sadness is not wallowing in hurt, it is a way of processing hurt. Sadness is not depression or withdrawal, it can fuel action and harden determination. Sadness has helped keep me alive and even helped me find happiness. The greatest mistake is to think sadness is just despair-lite. Sorrow isn’t a lesser form of despair- in some sense, it is the opposite of despair because despair posits that its all pointless while sorrow says that there is great value or potential that has been lost, and motivates us to honor what was lost. One can go into battle armed with sadness.

Even more damaging than anger is contempt. The more people you think are beneath your feet and worthy of only scorn the more you have lost because the more you have contracted into yourself and shrunk away from your own species. Anything- anger, sadness, paternalism- all of these are better answers to wrongdoing than contempt. I worry this sounds like high-flautin rhetoric, but I mean it in a straightforward sense. If you meet someone who holds a lot of people in contempt, you’ll see what I mean- and it scales with the number.

Perhaps there are two kinds of rage- a rage that covers over contempt, and a rage that covers over sadness. Ask yourself about something you’re mad about- if you run out of anger, what would be the primary emotion remaining? Sadness or contempt? Contemptous anger is much more dangerous than sad anger, and often the contempt is close to the surface. At the moment there is a debate going on in the Northern Territory of Australia about lowering the age of criminal responsibility down to 10 years old. In the headlines, this is framed in terms of community anger, but do you think these people are filled with implacable rage at the criminality of ten-year-olds- holding them as moral beings who have breached their obligations? Certainly not all of them that mime anger- perhaps not even most. A lot of them think that a certain type of ten-year-old is incorrigibly criminal. They regard them as non-moral subjects, for whom we must as quickly as possible abolish all barriers to ‘management’. Eventually, the overriding concern becomes not, “We must chastise these people” but instead “I don’t care what you do, just keep them away from me”.

Contempt and vengefulness are never positive emotions, but the worse you are, the worse they are for you. A bad person will use their contempt and vengefulness to hide from judgment of themselves, to avoid thinking about morality by dividing the world into three types of subject: passive, punishing and worthy of punishment.

Tragic consciousness- a profound openness to sadness- is the best way a human can hold onto love without sticking their head in the sand, and ultimately, it is far less contradictory to happiness than other negative emotions. Because sadness acknowledges the value in things, the lost opportunity, and the marred beauty, it is oddly close to happiness. Rightly understood, it in no way prevents us from acting to correct things.

Vengeance and vindication: People imagine that they want vengeance, when really what they want is vindication. In many cases, I think, the reason victims want a long sentence (when they do want a long sentence- it is a mistake to think they always do) is because they want society to assert that what was done to them was extraordinarily wrong. We have been taught that “the longest possible sentence” is the way to do that. We have been hoodwinked into thinking that we want vengeance because it is easier to give people vengeance than vindication. What we really want, I think, is the repair of the world. We want to be able to see each other, and be seen, and to have the truth of it all. Inflicting pain is a poor substitute for a real resolution. It might be the only substitute available sometimes, but it is still a poor one.

Even in our own lives, when we confront those who have done us wrong, rarely is what we want for them to suffer. We want them to know and understand that they have done wrong, for others familiar with the matter to affirm that they have done wrong, and for them to be prevented from doing wrong again. Imagine all of those things that happened to someone who had wronged you- they understood the wrongness of what they had done and why it was wrong, all those involved knew they had done wrong, and they were prevented from doing it again. Would you want them to suffer? If not, you don’t want vengeance, what you want is vindication.

Predatory lies: Everyone who reads about crime will eventually come across the following factoid, the public thinks crime is rising, but crime is at historic lows. Presumably, the blame falls on the media. Likewise, the media are also rightly blamed for encouraging the public to think that the sentences judges give are too lenient. In reality, when juries are asked what sentence they would give in their case, they find the judges if anything too harsh. This is all old hat- but isn’t it extraordinary? To prey on some of the most vulnerable people in society- those who we hold under our power, prisoners. To parasitize the public like a vampire sucking fear out of them, taking some of the substance of their light and leaving them cynical, scared, and cold to their neighbors who they now look upon as threats? To use victims to sell copies. Even aside from the effects on the criminal justice system through law and order auctions, it’s eating hope, sociability, trust, and compassion to shit out cash.

And here is the violent crime rate in the US over recent decades:

It’s amazing I even need to recapitulate this in 2024 but: The easiest way to refute a claim that something is not subject to influence by social structure, or is the non-contingent result of individual variation and choice, is to consider the enormous range of societies that have actually existed. Those graphs I gave above should put paid to the idea that crime is an individual problem, not a social problem, or that the crime rate is determined primarily by criminogenic genetics, etc- there is too much difference between societies and within the same society over time for this to be true. There’s a growing meme online that ‘squishy’ factors like social causes are bullshit, and it all comes down to genes, or race, or sourceless de novo maliciousness whatever but this is impossible on the numbers. If the murder rate can fall by a factor of 100 over 600 years in Spain, and further, more than halve in the last thirty years, clearly the main determinants of this variation must be larger social structures. This is not to deny a role for genes or to deny a role for indeterministic free will (although I do deny indeterministic free will), but a change of a factor of a hundred is incompatible with these being the main drivers of differences.

The gaze of punishment- punishment as a way of seeing, or a form of attention: Punishment leads to a certain way of seeing things. There is such a thing as seeing like a punisher. For the punisher. There is a clear code of rules, both understood and just. That code of rules has been breached as an act of pure discretion. The attention is narrowed to the moment of choice of the offender. Larger thoughts about structure or history are lost. This way of seeing creeps us on us, even as we try to resist us.

An example of the above is the way metoo was turned into a conversation about the flaws in the way our society thinks about consent, to a story about how some people had broken the clear rules as if problems with the ways we understand the rules wasn’t supposed to be much of the point. The structural point that there was a problem with the social world more broadly was lost, instead it became about the wicked actions of individuals, implying, at least to a degree, that they had breached through their individual responsibility a clearly existing and broadly just set of rules. This is what the gaze of punishment looks like. Even when we try to deny it, even when we punish because we absolutely must, punishment always draws us into this gaze, to a greater or lesser degree- all we can do is resist.

Another way to think about this is the implicit assertions of punishment.

a. There is a clear, qualitative moral difference between us and you (making us tend to forget our own sins and the fragility of goodness.

b. There is a clear and good system of rules you transgressed (making us tend to forget the rules are flawed, incomplete and somtimes vague).

c. You committed this transgression, in a sense, alone. Even if you had accomplices, they each committed their own crime, and you yours. (making us ignore the ways in which society itself transgressed).

d. I am harming you, but I should not feel bad about this- I should feel good about the harm I am doing because it is cleansing the world.

The rub is that even if we do not want to assert these things, we always risk doing so through punishment. When we engage in punishment, even when it is necessary and done with the best intentions, we speak words in an old language that we do not choose, often do not intend, and sometimes do not understand.

Refusal to accept responsibility: People often do not want to admit that they control punishment. Even as they see the perpetrator as wholly in control of their actions, they want punishment to be an impersonal force, acting through them. We can see this quite simply, as pundits and members of the public chabitually deny responsibility for punishment. Someone will be sentenced to 5 years for some relatively minor crime, and people of this sort will refer to it as “the consequences of their actions”, “If he didn’t want to face the consequences, he’s shouldn’t have done the crime”. as if they had no power over what the consequences were as if the consequences were automatic and beyond human choice, as if, in urging that “the consequences” should apply, they were not helping to make them the consequences. Consider people who say “Do the crime, do the time” as if there were some discrete amount of incarceration “the time” that had fallen from heaven as the appropriate amount, and we had no choice in the matter. Why do this? Because they know, on some level that the punishment in that particular case is cruel is cruel, hence they want to distance themselves from responsibility for supporting it. In a sense then, the very passivity of “do the crime, do the time” as a defense of this or that sentence- it’s unwillingness to give positive reasons- is an admission that the sentence is too harsh. It’s also an admission of cowardice on the part of the speaker.

But often focusing on criminal law as the way of managing a problem is itself is an attempt to avoid responsibility. “What can we do, these people keep spontaneously choosing to do the wrong thing- there is nothing in our power to prevent this, we can only punish the wrongdoers”. An example here is domestic violence- yes, we have to punish those who kill their families- but we could help prevent cases if there was a welfare state that allowed people to leave their partners and flee to safety. Now punishment is necessary in these cases, but we are kidding ourselves if we think that punishment can stop the actions of the often suicidal men who do these things. By accentuating the punishment we hide the broader failures and paint over the cracks. Punishment, as much as it is an insistence on a particular person’s guilt, is also a denial of the guilt of others and of ‘society’ and we can only mitigate, not wholly prevent this. Even if we do not want to see through the gaze of a punisher, punishment pushes us all towards seeing way.

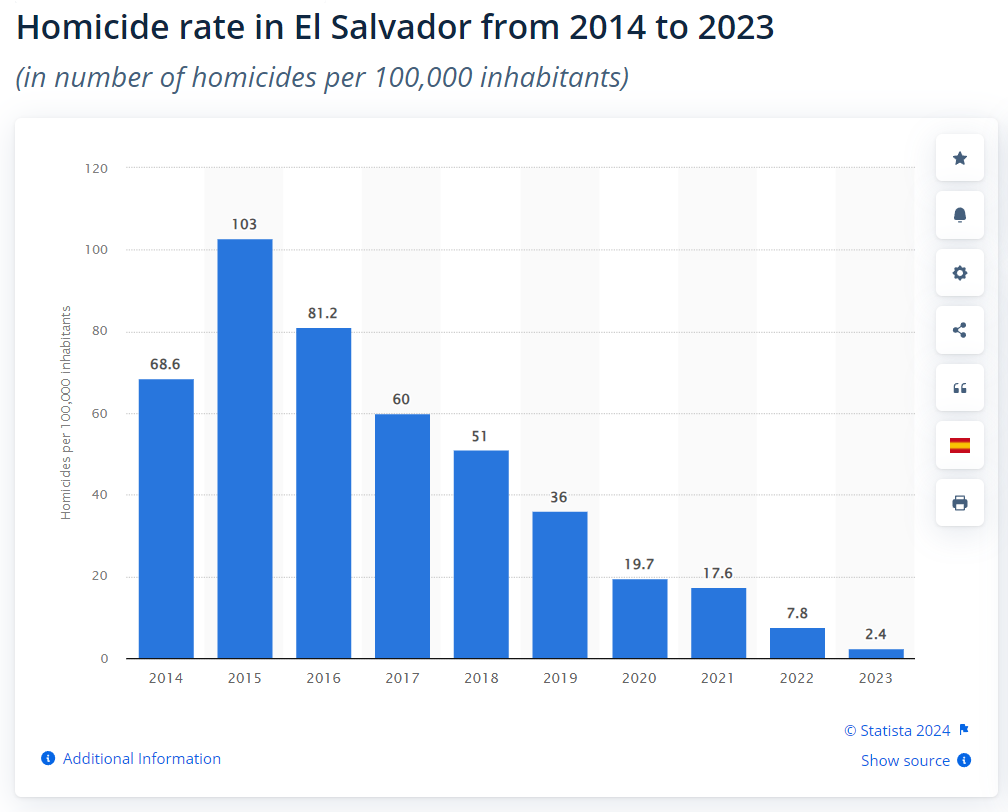

El Salvador: But enough of this namby pamby bullshit and soft considerations! You say. What about the costs and benefits of punishment? I want to start with something that is quite trendy to discuss at the moment, Bukele’s mass incarceration spree, which, at one point by my estimate, put about 4% of the adult male population behind bars

The crackdown happened in 2022, and certainly represents a discontinuity:

The trend was falling prior to this action. Let us say, at a guess, that the murder rate would have been 15 per 100,000 in 2023 without the crackdown, 6x higher, 792 lives saved. In exchange, about 60,000 additional people were incarcerated for a year, giving the tradeoff of about 75 incarceration years for each life saved, I’d estimate the average person murdered would have lived for about another 35 years. When one considers the various costs of a year of incarceration, this trade seems straightforwardly bad to me. I discuss this in further detail here.

Cost-benefit analysis: consideration of the costs does not support an unlimited regime of punishment. This has been clear for quite some time, the short-term impact on crime of incarceration at the margin is negative, but likely not worth the cost. The longer-term impact is unclear, but there are reasons to be pessimistic and think additional incarceration at the margin may actually increase crime. David Roodman has an excellent review here. This is concealed though by a long history of “one-sided rationality”- discussing the benefits of incarceration as if they were costless.

From a utilitarian perspective he main costs of incarceration are, in roughly descending order: (1): The value to the incarcerated of lost liberty (how much would you be willing to pay- even if you had to borrow- to avoid a year in prison?) (2): The costs to society of running prisons (3): The long term costs to the incarcerated (or the government) - economically, in terms of healthcare and lost earnings (4) Costs to families (5) Welfare costs of crimes committed in prisons (6) Costs caused by prison generated recidivism. None of these are light. Roodman estimates the costs at 92,000 dollars in 2010 currency- 132,707.56 in today’s currency. My estimate is closer to 200,000 in today’s US currency or about 300,000 in Australian dollars. Prison is, especially from a welfarist perspective, incredibly costly. The problem is that a lot of these costs often aren’t counted.

Now you get people saying “Hey, why are we counting harms to prisoners? Why are we counting harm to prisoners’ families? But this is moving the goalposts! Either we discuss these matters in terms of human dignity, the meaning of punishment etc., or we discuss them in terms of a utilitarian calculus. Almost anything can look rational if you refuse to count the chief cost. Barbarino and Mastrobuoni write: Notice that these costs do not include tax distortions (it costs more than 1 euro to collect 1 euro in taxes), rehabilitation of the criminal, retribution to society (DiIulio 1996), inmates’ wasted human capital, their potential increased criminal capital,38 their post-release decline in wages, and the pain and suffering of inmates and of their families (including that due to overcrowding). Well good for you! I too can get a cost-benefit analysis to support anything I want if I exclude the largest costs.

I am quite poor, spend many hours a week on this blog, and make it available for free. Your paid subscription and help getting the word out about this blog would be greatly appreciated.

"...metoo was turned into a conversation about the flaws in the way our society thinks about consent, to a story about how some people had broken the clear rules as if problems with the ways we understand the rules wasn’t supposed to be much of the point."

This is a really good point.

On the topic of vengeance versus vindication, I will recommend my friend Lara Bazelon's book Rectify. Lara has been a leader in the US on correcting miscarriages of justice, and in trying to find ways for the guilty to _actually make amends_ to those they've harmed rather than just being arbitrarily punished. (On the "miscarriages of justice front", there also was an amazing series on the podcast Suspect that covered one of her Innocence Project cases: https://podcasts.apple.com/in/podcast/suspect/id1580881826 )