I spend many hours a week on this blog and do not charge for its content except through voluntary donations. If you want to help out, would you mind adding my Substack to your list of recommended Substacks? It’s the main way people get new Subscribers. A big thanks as always to my paid subscribers.

Scott has posted an analysis of whether prison effectively prevents crime, which he kindly gave me an opportunity to read and give comments on before posting. I think it’s great, but I also think he’s holding himself back from explicitly drawing one of the most important conclusions warranted by the data: a utilitarian, even a utilitarian who discounts the pain of prisoners in some respects, should support reducing incarceration. The only way to avoid this conclusion is to make extreme assumptions about the directionality and strength of hard-to-quantify factors. The same is true of other welfarist approaches to public policy (Rawlsian, Prioritarian, etc.)

Statistically, when it comes to the effects of prison on crime, Scott and I arrive at broadly the same conclusion- although he arrives at it much more carefully. My sense is that Roodman’s Devil’s Advocate case in his Cost-Benefit Analysis is a reasonable baseline of the informed majority opinion to start the analysis. As Scott says:

“Would more prison be good or bad? We’d need to do a cost-benefit analysis. Surprisingly, Roodman does the best work here: after making his claim that costs and benefits mostly cancel out, he admits that most people won’t believe him, and tries to estimate the effect size in the “devil’s advocate” case where everyone else is right and he is wrong.”

Why am I attracted to this, instead of Roodman’s mainline analysis that seems to show prisons increase crime at the margins? Although Roodman seems smart and honest, I do not trust the results of endlessly relitigating statistics using instruments with a thousand points of freedom for the analyst. I prefer to work off the rough consensus of people doing quantitative work in the area.

As above, Scott is focused on the question of whether or not prison stops crime, perhaps because it’s an easier question to answer without getting into a culture war. I, however, am focused on the question of whether or not we should imprison more or fewer people. Scott does touch on this- here is Scott’s own conclusion on the topic:

The end result: if you don’t count the costs to the prisoner themselves, and you don’t use the more modern number, and you’re not in an expensive state like California, then the marginal incarceration-year saves society about $13,000.

If you do count those things, or you’re in an expensive state, the costs far outweigh the benefits.

Realistically, most people won’t care about analyses like this. They’ll be more interested in the unquantifiable costs and benefits, including:

The “benefit” of feeling like justice has been done and an evil deed has been avenged.

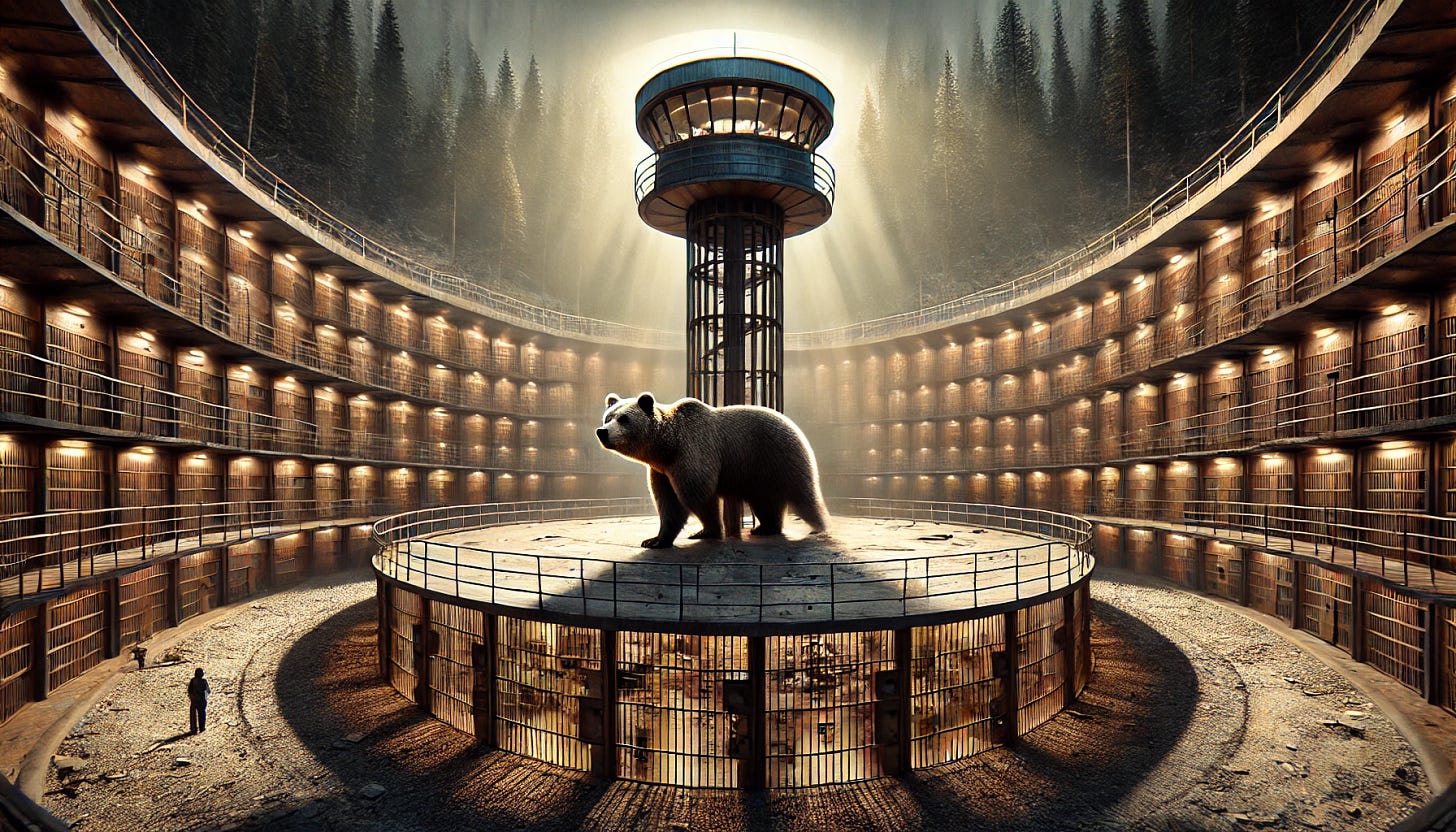

The “cost” of becoming the type of person who puts their fellow humans in cages.

The beneficial effects on non-crime forms of public disorder - the prisoner can no longer litter or harass people on the subway.

The cost of within-prison crimes. Even if you dismiss the suffering of a prisoner caused by prison itself (on the grounds that justice demands it), prisoners getting raped or shanked was not part of their sentence and should plausibly get counted on the debits side of the ledger.

The cost to innocents. Nobody knows what percent of prisoners are innocent, but I have seen estimates from 2 - 5%. Even if you dismiss the suffering of a guilty prisoner, you probably don’t want to dismiss the suffering of an innocent one.

The benefit from increased urban density. Ben Southwood claims that this may outweigh all other costs and benefits in the equation. His argument goes: when cities are crime-ridden, people move to the suburbs. The suburbs are less dense than cities, driving up housing costs and decreasing the agglomeration effects crucial for technoeconomic progress. Therefore, crime is responsible for a significant portion of the housing crisis and of lost GDP from the Great Stagnation.

The cost of imprisonment to families and communities - for example, now the prisoner’s children are without a father, the prisoner’s family is without a son/brother/etc, the prisoner’s corner store is without a customer, etc.

Later in the piece, Scott writes:

Prison is less cost-effective than other methods of decreasing crime at most current margins. If people weren’t attracted by the emotional punch of how “tough-on-crime” it feels, they would probably want to divert justice system resources away from prisons into other things like police and courts.

Adding:

I’m putting this last one in bold because I don’t want people’s takeaway from this post to be “Aha, prison decreases crime after all, we should do much more of it!” I think prison has greater than zero effect, but that untargeted longer sentences aren’t the most effective or cost-effective solution to crime.

So Scott comes close to prison reductionism, but I would argue for taking the final steps. I think there’s a case to be made for focusing on the question of cost-benefit analysis, although it will immediately turn into a political s******** because I think the cost-benefit analysis of prisons is where most of the immediate progress is to be made. We have enough evidence to restrain effect sizes to a relatively narrow band- narrow enough for a preliminary analysis of the practical question. Narrowing it down much further in even an approximately uncontroversial way is unlikely. Of course, people might reject the results of a cost-benefit analysis and, e.g. still continue to support or oppose further incarceration on deontic grounds. However, a CBA showing costs outweigh benefits is at least a substantial contribution to the public debate.

I am alarmed at the way in which some people adjacent to the rationalist community have begun talking as if there was some kind of “warrant of science” or some kind of clear utilitarian result in favor of the conclusion that locking more people up will increase social welfare. This is not true, indeed I’d argue that if you are a strict utilitarian and consider prisoners’ welfare it’s hard to avoid the result that social costs outweigh social benefits. I take Scott’s point about most of the benefits being unquantifiable- but if you care about prisoners’ welfare, there is a huge net social cost among the aggregated quantifiable factors. If you’re a utilitarian, and by extension, if you’re a Prioritarian, you should not be supporting additional incarceration. We should make people aware of this, since some people, based e.g. on glib discussions seem to think the opposite conclusion has been “proven”.

Here are some points that I think are indispensable:

1. We should at least count the disvalue of crimes that occur in prison against incarceration. Even if you think prisoners have in some sense “earned” their suffering, they surely have not earned such. My view, from which some might demur, is that people who don’t care about assaults, rapes, etc. that happen in prison do not deserve a seat at the table.

This is important because the crime rate in prison is quite high- and perhaps especially for very serious crimes. It greatly affects the CBA.

2. Pain and suffering to families should and can be counted since they have done nothing wrong. It would not be at all difficult, by the standards of CBA. We can quantify these costs by using willingness to pay analysis, or looking at how much people pay for family members’ lawyers or… We just haven’t yet because people do not care about prisoners’ families. I would not be surprised if this factor alone outweighed the 13,000-dollar surplus. Pain and suffering is not just emotional, it is also present economically e.g. in child poverty.

3. Foregone income by prisoners has social as well as personal costs. Foregone income also extends beyond time in prison due to long-term unemployment and further social costs (and costs on prisoners’ families) are inflicted by damage to prisoners’ health inflicted by prisons.

4. If we do not count the suffering included in incarceration at all, we arrive at something of a paradox. Theoretically, we could stuff people in boxes and shovel in food through a slot. This would greatly reduce cost- which, on a view on which we should not count costs to prisoners- would be a pure win!

The point is that surely we should include costs to prisoners in our calculation when they get below some minimum standard of decency which is not a legitimate punishment.

5. Theoretically, by the normal standards of cost-benefit analysis, we should also engage in what is called a cost of funds adjustment representing the deadweight loss of taxation. This accounting of the damage done to the economy through tax extraction is often set at about 20% of the total value of the taxes collected. The cost of funds adjustment alone could, depending on what it’s set at, obliterate the 13,000 dollar surplus. Now Ng makes an argument, called “A dollar is a dollar” that the cost of funds is set by how redistributive a given bit of spending is, so if a bit of spending has no redistributive effect- if it benefits everyone in exact proportion to their contribution to funding the project- then the cost of funds is zero for reasons I won’t get into here. Also, because I’m a socialist hack, I think that cost of funds estimates are often greatly over-estimated and the whole framework is poorly thought through, but if you disagree with me on these things, as my rightwing and centrist readers surely must, then you should think there’s this massive extra set of costs that Roodman and Scott haven’t factored in.

The following conclusions seem hard to avoid:

For the pure utilitarian case, even acknowledging the importance of intangibles, when we factor in things like prisoner suffering, crimes against prisoners, family suffering, etc. We can say we have strong utilitarian evidence against further incarceration, and for reducing incarceration at the margin. In today’s dollars, I’d say the net total social costs of quantifiable factors, taking into account the welfare of prisoners, is north of 100,000, especially when we consider the ballooning cost of incarceration.

Define a moderate utilitarian position as one that takes prisoner suffering into account only insofar as it is not a legitimate punishment for their sentence. Non-legitimate aspects of what happens in prisons. would include crimes in prison, the effects of poorly run and maintained prisons, and forms of torture like solitary confinement, etc. The moderate utilitarian would also take into account costs to families, costs to the state arising from later health problems and unemployment, etc.

When we factor in family suffering, crime in prison, the barbarous quality of American prisons, social costs of loss of income and loss of future income, etc. I think we probably also substantially exceed the 13,000-dollar social surplus to additional incarceration in Roodman’s devil’s advocate analysis. Even on this moderate utilitarian view, and even accounting for the importance of intangible factors, I think we have evidence against further incarceration. I would challenge anyone to produce a plausible back-of-the-envelope calculation on which this is not true.

I suspect even on a selective utilitarian analysis in which prisoners’ interests are simply not counted at all, prison likely isn’t optimal at the margin- but I’ll leave that aside here as that would take a much longer discussion. Notable effects even the selective utilitarian has to consider are: 1. Costs to families and children, 2. Costs to the state through long-term health and unemployment effects 3. Costs to the economy through reduced output. 4. Cost of funds adjustments, if any.

Beyond the recent pretenses to more incarceration just being “commonsense” based on flawed and glib social science, I also question the deep faith on parts of the right that even a big reduction in crime would make all that much difference in their lives. I’ve read some people who say they think it would create a utopia! That’s crazy. A 50% reduction is equivalent to a couple of years of economic growth, tops. The psychology of obsession with crime has already been done to death- but the insistence of the neo-reactionary that the sine non qua of good governance rationally must be crime is perplexing to me. I always like to bring this graph up in the discussion to put things in perspective:

Did you see that study about how children whose criminal fathers who randomly ended up spending more time in prison ended up doing better?

If less than 1% of the population is in prison then presumably those people are close to being the top 1% in terms of being dysfunctional in an antisocial way. Likely a net negative to people around them, whether at home or at work.

"a big reduction in crime would make all that much difference in their lives. I’ve read some people who say they think it would create a utopia! That’s crazy."

In some places it would be the difference between kids playing the streets and families in parks versus being afraid to go outdoors. What do you think about places with rampant public disorder, are they over-incarcerating people? Maybe they just need more policing, but you don't seem to be making that argument.

Besides urban density, if we're being utilitarian perhaps other things to consider is how crime affects people's politics(making progressives look insane?), fertility(too unsafe for kids?) and long-term thinking in general(world seems too unpredictable with random crime?).

An area that seems like it might be particularly tractable is reductions in very long/life sentances - in the USA "life without parole" really does mean "you will be in prison until you die". I am unsure exactly how you'd go about changing this but I think you might be able to make progress on shortening these sentances via pardons/commutions.

Older people are unlikely to reoffend so from a cost benefit analysis this is not a good use of money. I realize people care more about "justice" than utilitarian calculations like that, but I think the average person would feel uneasy about sentancing a man to serve 40 years for a crime he committed 30 years ago. It won't be uncontroversial but I don't think you'd get quite the same opposition as you would for more immediate crimes - perhaps there's something to be said for the UK approach of sentancing murderers to "life" and then letting them out in 15 years time conditional on good behaviour, although there are still "whole life" terms that really do mean exactly that.

Maybe there are some people who "need" to be locked up for the rest of their life for pragmatic or moral reasons, but I feel like the typical case is someone who murdered another person while young and impulsive and is now very aware that that was both immoral and stupid, and I think the average person (read: voter in a democracy) is willing to be forgiving in that situation.