I have never heard an in-depth discussion by a normative ethicist about the relationship between ethical and political beliefs. I mean this in a somewhat special sense. Obviously, I have heard people argue that certain ethical commitments imply certain political commitments and vice versa, but I’ve never heard a philosopher discuss the obvious point that, empirically, there is massive covariance between political and ethical views, and maybe this should inform our philosophical thinking about both politics and ethics. I am sure such discussions exist, (e.g., some philosopher somewhere has to have written a paper on Haidt’s stuff) but I think that my experiences suggest they are not especially common. Why?

Consequentialism and politics

It’s not because these correlations don’t also exist among philosophers. 33% of Egalitarian philosophers are consequentialists, whereas 18% of non-egalitarians are consequentialists according to the philosopher’s survey. This is despite well-publicized (and I think completely overblown) claims that utilitarianism is incompatible with philosophical egalitarianism due to the leveling down objection.

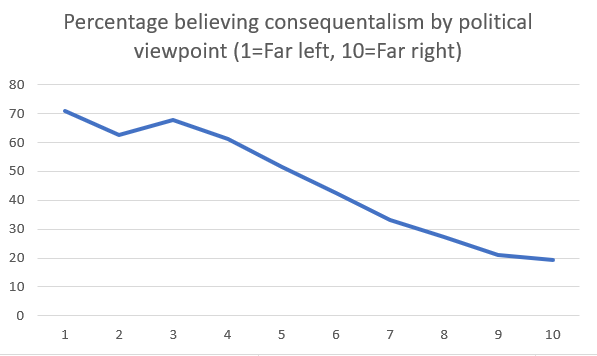

And the public? Consider this data from the Slate Star Codex user survey. This is hardly the general public, but I think they’re interesting as a sample of non-philosophers who know something about ethics:

From 70% to 20%! For those without a background in the social sciences: you don’t get relationships of this strength often when it comes to people.

Impartiality and politics

The relationship isn’t just between consequentialism and political views, it extends to much more visceral questions, and, I suspect, probably ultimately originates in these differences. In a recent survey, I made a scale of ethical impartiality or, perhaps we should say instead, broadness of compassion. Each question was scored 0-4, with higher scores representing a greater degree of impartiality.

Your child will die unless you press a button that kills ten random children- if you push that button, your child will live. Would you prefer to be the sort of person who would push that button, or not?

A building is burning. You only have time to save one of two people. The person that is closest to you in the world, or a scientist who will, if he survives, cure a common and deadly disease. Who do you save?

Would you rather save 50 randomly selected people from your own country or 100 randomly selected people from around the world?

Would you prefer 500 dollars for yourself, or 10,000 dollars spent on saving children dying in a famine?

I also asked people how they would vote and compared this with impartiality scores. My sample of Republicans was, unfortunately small, but the difference between people who said they would vote Republican and people who said they would vote Democrat was huge. Despite the small sample of Republicans, the result was highly statistically significant (P=~0.001)

There is a higher standard deviation among Republicans. The sample is small, etc. but that’s at least vaguely consistent with my previous work suggesting there may be different types of conservatives: with the two ‘perfect’ types being, at their most extreme:

Though much more research is needed etc. etc.

Again, I must emphasize that these effect sizes are staggeringly large for the social sciences.

Conclusions:

I have written in the past about how consequentialism needs to shake off its inegalitarian reputation. In theory, consequentialism can lead to inegalitarian outcomes. However, in practice, consequentialism is vastly more egalitarian in its consequences than the policy platform of any party of government in, say, the OECD.

We need to stop pretending that both sides of politics ‘want the same things’ but disagree on how to get them. There are a thousand disproofs of this and conflict theory is a true description of many aspects of political disagreement. I invented dichotomizing conflict and mistake theory as categories partly to show that conflict theory is right, but instead, people seem to have decided conflict theory is evil or nasty. Weird. It’s just a description of how things work. People don’t want the same thing and they fight over it. What could be more obvious?

Philosophers should think more about how the battle between partiality and impartiality penetrates ordinary political thinking. Also, philosophers should think more about the political dimensions of the debate over consequentialism. In general, philosophers think more about politics as it is. I don’t mean in the sense of preferring non-ideal to ideal theory, I mean in the sense of looking at the categories and formations that exist in “civilian” non-philosophical political discourse, and trying to interpret and evaluate these categories. What, from a philosophical perspective, is the meaning of categories like “leftwing” and “rightwing” for example?

Politically, these results indicate some priorities for the left:

Consider trying to increase broad compassion/ethical impartiality in the population, and the mechanisms by which it might be achieved. Maybe even try to promote consequentialism?

Consider how to appeal to people who haven’t got broad compassion. How to make the case that leftism is good for them, their family, and their close community

Consider how to split off elements of the right who are consequentialist and/or possess broad compassion.

More research on the relationship between impartiality and conservatism, and consequentialism and conservatism, is necessary. substantial good research on impartiality already exists but we need more. The effect sizes alone are big enough to justify the research.

Effective alturists should probably at least be aware that their fundamental ethical premises are, empirically, strongly associated with leftism. What they should do with that information I’m not sure.

This is an interesting question!

I do think you may be wrongly implying that consequentialism and Nietzschean selfishness are the only options. I'm thinking of how an extremely kind, compassionate, and thoughtful Christian online friend of mine would answer these questions. He fully accepts the Christian ideal of universal love--he's the furthest thing in the world from a Nietzschean--but is aggressively anti-consequentialist in his moral views.

For 1), he would absolutely *not* press the button to kill ten other children to save his own--since killing innocent people would be inherently, deontologically evil, even if for an altruistic cause. (Unlike a consequentialist, though, he'd be equally unwilling to kill *one* innocent person to save ten others.)

For 2), I know for a fact that he *would* choose to save his own loved one over the life-saving scientist. Indeed, he'd go further than this--he once told me that he would choose to save his own child over some large number (I don't remember which one) of other innocent children, if he was forced to choose. He said that this would be the objectively morally correct thing to do, not because his own children were inherently more valuable, but because we have special moral obligations to those close to us. But, as an deontologist, he makes a fundental moral distinction between merely *not helping* and actively *harming*.

For 3), I *don't* think he would choose to save a smaller number of his own fellow-citizens rather than a larger number of foreigners, since he's generally negative about nationalism--but I'm less sure about this than the other questions.

For 4), he would *definitely* choose to have a much-larger sum spent aiding the starving than given to himself. This question almost seems too easy--it's a pure issue of selfishness, not the more challenging one of 'groupishness', of special moral obligations to those close to you. Asking if people would prefer a smaller sum be given to the poor *in their own community* rather than a larger sum to those in greater need abroad would be a better way of getting at the difference in moral intuitions here.

Haidt is a bad faith actor, the kind referred to on the Internet as a "concern troll". He presents as a liberal, but his aim is to normalize bad behavior by conservatives. Pre-Trump, this was done by positing a concern for decency and legitimate authority, now it's more about in-group loyalty